Jairo Mora Delgado

Research Group Sistemas Agroforestales Pecuarios,

Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia,

Universidad del Tolima, Ibagué, Colombia

jrmora@ut.edu.co

Recibido: 16 de mayo 2013 • Aprobado: 17 de junio de 2013

Resumen:

Las sociedades rurales del área andina se caracterizan por los pequeños propietarios, campesinos principalmente. Un estudio fue llevado a cabo en 39 pequeñas propiedades en las áreas de cultivo de café de Tolima (Colombia). Estas propiedades fueron clasificadas en tres tipos: pequeñas, medianas y grandes fincas.

Para recabar la información, se recurrió a la observación y las entrevistas. Diferentes formas de crédito y de capital social fueron identificadas, tales como la pertenencia a una red, la participación en programas de asistencia técnica, el entrenamiento e intercambio de relaciones entre vecinos.

La pertenencia a redes constituye una forma de interacción social que puede ayudar a mejorar la calidad de vida de los hogares. Por este medio, las comunidades campesinas pueden tener acceso a entrenamiento e información, o bien a la participación en redes de aprendizaje organizadas por cooperativas, organizaciones religiosas y ONG, o simplemente formas intangibles de beneficio, tales como el reconocimiento social. En las fincas pequeñas y medianas, la importancia de pertenecer a una red fue preponderante (71% y 77% a medianos y pequeños respectivamente).

Por otro lado, el intercambio entre vecinos constituye una forma recíproca de interacción muy generalizada en las sociedades rurales, principalmente entre los pequeños propietarios (66% practica el intercambio local). Esta es la forma en que las familias tienen acceso a las ganancias agrícolas o a los productos por medio de las prácticas de reciprocidad. Este tipo de relación fortalece los lazos comunitarios y asegura tanto los suministros como la circulación local de sus productos, principalmente semillas, animales, frutas fertilizantes orgánicos e información. El nexo con instituciones, por medio de la asistencia técnica, establece una forma de capital social: 95%, 77% y 66% de los agricultores (pequeños, medianos y grandes, respectivamente) mantienen relación con algún tipo de intitucion de asistencia técnica y servicios de estension, la mayor parte llevadas a cabo por organizaciones de productores (comité de cafeteros) e instituciones locales de asistencia técnica (UMATA). En conclusión, el capital social ha contribuido para mejorar el bienestar de las familias campesinas en el área rural andina que fue estudiada.

Palabras claves: crédito, campesinos, capital humano, desarrollo comunitario, bienestar social

Abstract

Rural societies of Andean area are characterized by smallholders, mainly, peasants people. A study was carried out in 39 households of coffee growth areas from Tolima (Colombia), following the livelihoods approach. Those households were classified in three types: small, medium and big farms. To achieve the information, we used surveys and interviews. Different forms of trust and social capital were identified, such as belonging to network, participation in technical assistance programs, training and interchange relationships among neighbours. Belonging to network constitutes a form of social interaction that can improve life quality of homes. By this mean, peasant communities can access to training and information or participation in learning network organized by cooperatives, religion organizations and NGO’s, or simply, intangible forms of profit, such as social recognition. In the smaller and medium farms the importance of belonging to network was predominant (71% and 77% to medium and small respectively). On the other hand, interchange between neighbours is a reciprocal form of interaction very generalized in the rural societies, mainly in smallholders (66% practice local interchange). It is the way as the families have access to agricultural inputs or products by means of reciprocal practices.This type of relation fortifies the communitarian ties and assures both a supplying and local circulation of its products, mainly seeds, animals, fruits, organic fertilizers and information. The linking with institutions, through the technical assistance, establishes a form of social capital: 95%, 77% and 66% of farmers (small, medium and big farms, respectively) keep relationships with some technical assistance institution and extension services, the most of them carried out by producers’ organizations (Comité de Cafeteros), local technical assistance institutions (UMATA). In conclusion, social capital has contributed to improve wellbeing of peasant households in the studied rural Andean area.

Keywords: trust, peasants, human capital, communitarian development, social wellbeing

Introduction

The concept of social capital was popularized byPutnam (1993) and since then the rural development has become increasingly enthusiastic about the potential utility of the concept to explain the diversity of relationships between communities and institutionsin order to build network’s actions. Before that, Bourdieu (1986) had defined the notion of social capital as "an attributeof an individual in a social context" and he empathized with the capacity of individuals to acquire social capital throughpurposeful actions and thus transform socialcapital into conventional economicgains, submitted it "at nature of the social obligations, connections, and networks available".

There are many views about the social capital in the literature, but the common pointbeing that the social capital is the existing stock of social relationships in a society (Murthy and Murthy, 2002). However, Portes (1998) suggested that despite its current popularity, the term does not embody any really new idea, because that involvement and participation in groups, with their positive consequences for the individual and the community, has been a notion proposed by Durkheim and after him by Marx. Especially, Marx established a distinction between an atomized class-in-itself and a mobilized and effective class-for-itself. In this sense, the term social capital simply recaptures an insight present since the very beginnings of the sociologists discipline (Portes, 1998).

However, in the Andean rural societies social capital is a good framework to analyze the cultural dynamics, in which the reciprocal and non reciprocal social relations are important like likelihoods strategies. Thesocial relationships constitute the institutions describing formal or informal set of rulessuch as laws, regulations and standards (Murthy and Murthy, 2002). Earlier definitions of social capitalemphasized that it constitutes informal institutions and lies beyond the formal regulationsand organizations, they could be: obligationsand expectations, information channels, social norms (Coleman, 1988) and trust relationships (Fukuyama,1995).

Trust entails a willingness to take risks in a social context based on a sense of confidence thatothers will respond as expected and will act in mutually supportive ways, or at leastthat others do not intend harm (Onyx, 2004; Fukuyama, 1995; Misztral, 1996)

Pretty (2003) distinguished social capital into three dimensions: bonding, bridging and linking. For that analytical discourse he recaptured a key distinction between bridging and bonding social capital, previously analyzed by Putnam (2000). Thus, bonding social capital appears to be characterized by dense, multifunctional ties and strong but localized trust. They provide the basic source of the individual’s identity and sense of meaningfulness within the community and these ties provide personal support for social action at the communitylevel (Onyx, 2004). Bridging social capital implies a different set of norms, based on alooser form of networks, as the capacity to access resources such as information, knowledge, and finance from sources external to the organization or community in question (Woolcock and Narayan, 2000).On the other hand, linking social capital is the capacity of groups to gain access to resources, ideas and information from formal institutions beyond the community (Pretty, 2003).

Rural societies of Andean area are characterized by smallholders, mainly, peasants people. Unfortunately, the general image, at world level, of this area has been related to poverty, environmental degradation and migration process, however an important diversity of livelihoods can be found, especially, social capital, which has been very important for rural development rural, actually, different works have shown how the local social capital have clearly played an important role in influencing trajectories ofenvironmental and socio-economic change in the Andes (Bebbington; 1997, León, 2007). The aim of this paper was to assess the characteristics and dimensions of social capital and how social capitalinteracts with other livelihoods in households of rural area. Thus, the goal of this analysis was to measure evidences and perceptions of social capital and thrust relations of a peasant community in an Andean area of Colombia South America, in order to contribute to understanding of the importance of social capital in the rural Andean area of Colombia, South America.

Methodology

As part of a larger research (Calderón and Gómez, 2007), from which I used the data base, the research design of this study was descriptive in nature. The first part of inquiry aimed to review secondary information about socioeconomic aspects and biophysics events related to modifications of landscape, mainly the process of land use change toward an agricultural and livestock landscape, dominated by coffee plantations. After that, in 2006, a simple random sample of farmers was chosen to participate from 2006-2007 in the project. Thus, the target population for this study was 39 households from four municipalities (Anzoátegui, Villahermosa, Fresno and Líbano) of Tolima (Colombia). The main economic activity of this area is the growth of coffee, but the livestock activities are increasing in the household’s activities portfolio. The area is located at 1100 – 2100 m.a.s.l. average temperature is 19 ºC and precipitations of 1000 – 3000 mm per year.

To collect the information, we used surveys and interviews developed for the larger study, in which a data base was done. The portion of the instrument related to the objectives of this study sought to measure each subjects' cooperative behavior and trust ties of local people.Different forms of trust and social capital were identified, such as belonging to network, participation in technical assistance programs, interchange relationships among neighbours and participative training.

Three households-types (small, medium and big farms) were defined by using cluster analysis of multivariate statistics (Calderón and Gómez, 2007). Thus, I am describing the characteristics of reciprocity, behavior (cooperate, thrust, social relations, give-and-take, etc), and determine how levels of cooperation and reciprocity relations directly affect access to available resources and wellbeing of rural households.

An complex index of social capital was constructed based on the number of participations in: belonging to network, technical assistance, interchanges and training. Calculations were done using the following formula:

| SCIM = | (E+ TA+ RI+ T) / 4 |

| N |

Where: SCIM means social capital index based in the average arithmetic, higher index means best condition of households; E is Belonging to networks (# groups); TA is Technical assistance (# Linking) ; RI is reciprocal interchanges (average habitual interchanges); T is training as presence (1) or absence (0); N is the number of households and 4 is the number of simple indicators.

Results

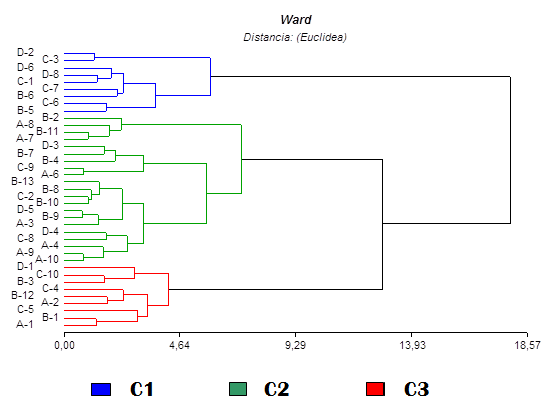

With data from each household clustering was performed using the technique of cluster analysis (CA) by the Ward method. This procedure allowed households grouped according to their similarity to the variables analyzed. Ward method groups elements between which there is a minimal variability, and thus form groups including variability are maximized. Cluster analysis showed three types of households (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dendrogram of cluster analysis of peasant farms in study area from Tolima

First of all, it is important to describe some characteristics of human capital. All the households had adult people, predominating ages up 40, especially in households of medium and big farms (43% and 38%, respectively), which suggest a tendency to migration process of young people from rural areas to urban areas, looking for better opportunities for study or job. Probably this aspect is related with gender distribution in the households analyzed, where in big and medium farms the majority of people were women, especially in big farms (59%), it is because, under an Andean peasant culture, only the boys are sent to study at urban areas.

The households were similar in terms of education levels, predominating people with primary or incomplete secondary studies (69%, 72%, 62%, in big, small and medium farms, respectively). An average of 7% in all households had attained university studies. However, 5% of the small farms lacked formal education compared to big (3.5%) and medium farms (4%).

Social interaction

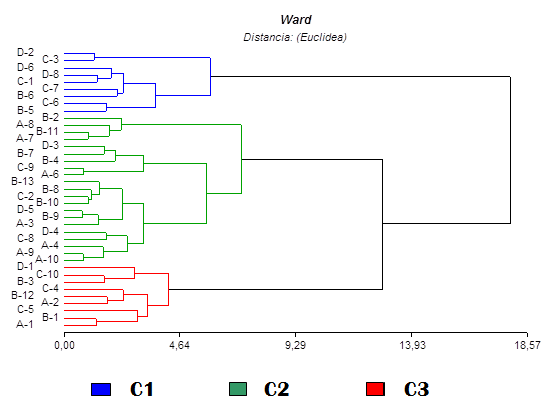

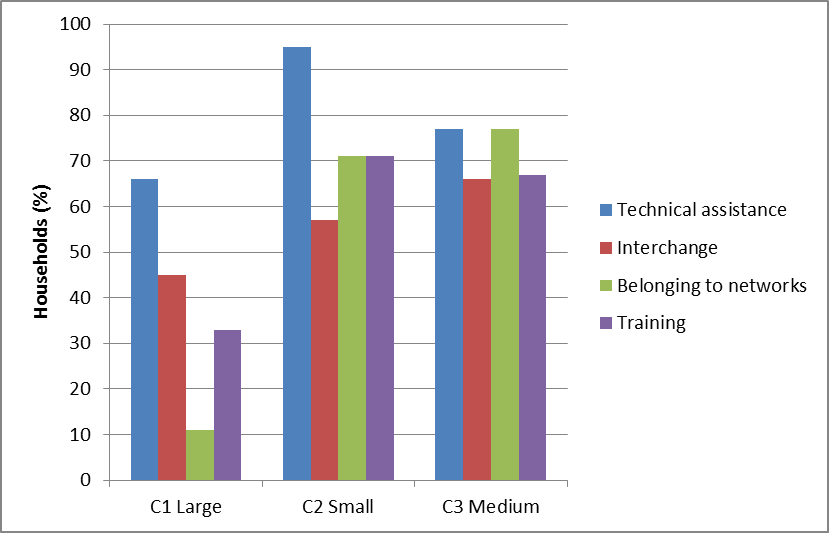

In the smaller and medium farms the importance of belonging to networks was predominant (71% and 77% to medium and small respectively) and this strategy has been widely spread, probably because belonging to network (Figure 2), like cooperatives, associations, action communitarian groups, religious groups (pastoral social) and producer organizations to technical training (i.e. grupos de amistad), constitutes forms of social interaction that they can improve life quality of homes. By this mean, peasant communities can access to training, interchange of products and information or simply, intangible forms of profit, such as social recognition. Actually, there is a close relation between belonging to network and technical training, because it is common to obtain skills by mean of workshops, short courses or field days organized by different social organizations. In other words, it could be a form of bridging social capital, because belonging to networks constitutes a strategy to achieve structural relations and networks between institutions and communities, involving coordination or collaboration with other groups (Narayan and Pritchett, 1999). Such bridges are likely to be mediated by trusted intermediaries, generally foreign, who are sufficiently well-known by all parties to form a conduit between otherwise disparate orisolated networks (Leonard and Onyx, 2003). This constitutes a reciprocal double way relation.

At respect, Abenakyo et al (2007) suggest that increase in skills is usually attributed to the interactions within and between the existing networks, which facilitate local knowledge and information sharing; it is further enhanced by bonding and bridging social capital and this contributes to build social capital, as a framework which supports learning through the horizontal and vertical interactions in the networks. Putman’s (1993) analysis of civic traditions called that “horizontal” associations, inwhich members relate to each other on an equal basis.

Figure 2. Social interaction forms of peasant households from coffee growth areas from Tolima (Colombia).

On the other hand, interchange between neighbours is a reciprocal form of interaction very generalized in the rural societies, mainly in medium and smallholders (66% and 57%, respectively). It is the way as the families have access to agricultural inputs or products by means of reciprocal practices, which could be interchange or tradeoffs of products or services. Pretty (2003) named it as bonding social capital to refer to the symmetric relations between homogenous people or communities, which build social cohesion needed for everyday living (Abenakyo et al, 2007). This type of relation fortifies the communitarian ties and assures both a supplying and local circulation of its products. The main product or services interchanged in the analyzed community were: seeds, hens, fruits, organic fertilizers and information.

The linking with institutions, through the technical assistance or agricultural training, establish a form of social capital: 95%, 77% and 66% of farmers (small, medium and big farms, respectively) keep relationships with some technical assistance institution, extension services or participation in learning network, most of them carried out by private producers’ organizations (Comité de Cafeteros), local technical assistance institutions (UMATA), cooperatives, religion organizations and NGO’s. This mechanism of social interaction could be named linking social capital;which is the capacity of groups to gain access to resources, ideas and information from formal institutions beyond the community (Pretty, 2003) and mechanisms of social support (public or private) or sharing of information across both governmental or not governmental programs. The technical assistance, as mechanism of social interaction was important for households of the biggest farms, concerning other interaction strategies, but it was the group with less number of users of technical assistance. On the contrary, 95% of households from small farms (C2) used this service from public or private institutions (UMATA or Comité de Cafeteros, respectively).

Households of big farms had the worst index of social capital (0.53), meanwhile, medium farms had the best index (1.1) and very close to this was obtained by small farms (0.96). Probably it is related with misconceptions imprinted to reciprocity and trust relationships (networks and interchange) by households of big farms, which is expressed in a low participation in this forms of social capital. In contrast, medium and small farms gave more importance to participate in building social capital.

However, there is an inverse relationship between income and the levels of social capital, because the best incomes were achieved in big farms, where the social capital index was lower. But, it is coincident to the best social capital index of households of medium farms with the best per capita incomes. Other studies (Abenakyo et al 2007) about the relationship between income and the levels of social capital, revealed that the difference have not been statistically significant.

Table 1. Financial and demographic indicators of households from Andean area of Colombia (South America)

Householdtype |

|||

C1 Big |

C2 Small |

C3 Medium |

|

Agricultural area (ha)* |

17.5 |

5.3 |

9.3 |

Households (No.) |

9 |

21 |

9 |

People/household (No.)* |

4 |

5 |

2 |

Annualincomes (US$/farm)* |

34,613 |

13,900 |

20,892 |

Incomes/ha (US$)* |

1,978 |

2,623 |

2,246 |

Per capita incomes (US$/year)* |

8,653 |

2,780 |

10,446 |

*Average per cluster

Social capital could affect positively other capitals, because by mean of reciprocity relations they might diminish operative costs by cooperative work; improvementof economical relationships and increasing knowledge and innovation (Ellis 2000). Thus, households with better social interaction probably could have more participation in projects andaccess to productive resources.

Conclusion

Social capital is very important to improve social wellbeing of both rural households and communities, by means of supporting learning processes, cooperative actions and access to innovations and products, through interaction, horizontal and vertical. Therefore, strengthening social capital is a powerful way to improve rural development which requires consistent and effective approaches to build and reinforce the social and human capital. In conclusion, there was a positive relationship between the level and dimension of social capital and access to livelihood assets implied in the households of Andean rural area from Colombia.

References.

Abenakyo, A; Sanginga, P; Njuki, J; Kaaria, S; Delve, R.2007. Relationship between Social Capital and Livelihood Enhancing Capitals among Smallholder Farmers in Uganda. AAAE Conference Proceedings (2007), 536-541.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. Forms of Capital, in Hand Book of Theory and Research for the

Sociology of Education. John G. Richardson, ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 241-

60.

Bebbington, A. 1997. Social Capital and Rural Intensification: Local Organizations and Islands of Sustainability in the Rural Andes. The Geographical Journal, Vol. 163, No. 2.

Calderón, J.C., y S.M.Gómez (2007). Evaluación bioeconómica de modelos pecuarios y planteamiento de diseños alternativos mejorados en fincas de los municipios de Anzoátegui, Villahermosa, Fresno y Líbano (Tolima). Trabajo de Grado para optar al título de M.V.Z., Universidad del Tolima. 151p.

Coleman, James S. 1988. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 128-56.

Ellis, F. 2000. Rural livelihoods and diversity in development countries. Nueva York: Oxford University Press,273 p.

Fukuyama, F. 1995. Trust: the social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press: New York: Free Press.

Leonard, R. and J. Onyx. 2003. Networking through loose and strong ties: an Australian qualitative study.Voluntas,14 (2): 191–205.

León, G. 2006. Estrategias de vida en familias cafeteras y su relación con la riqueza etnobotánica de fincas en el departamento de Caldas, Colombia. Tesis M.Sc. Centro Agronómico de Investigación y Enseñanza CATIE. Turialba, Costa Rica.

Misztral, B. 1996. Trust in Modern Societies: the search for the bases of social order. Cambridge: PolityPress.

Murthy M.N. and S. Murthy. 2002. Cultural Heritage: A Fusion of Human Skill Capital and Social Capital. Nueva Delhi: Miranda House College, Delhi University, 22 p.

Narayan, D. and L. Pritchett. 1999. Cents andSociability: Household Income and Social

Capital in Rural Tanzania. EconomicDevelopment and Cultural Change, 47(4), 871-897.

Onyx, J. 2004. The Relationship Between Social Capital and Sustainable Practices: Revisiting “The Commons”. In: H. Cheney, E. Katz, F. Solomo (Eds.). Sustainability and Social Science, Proceedings. Melbourne (Australia): The Institute for Sustainable Futures, Sydney and CSIRO Minerals, Melbourne. On line http://www.minerals.csiro.au/sd/pubs/Onyx_Final.pdf

Portes, A. 1998. SOCIAL CAPITAL: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998. 24:1–24.

Pretty, J. 2003.Social capital and the collectivemanagement of resources. Science 32: 1912-1914.

Putnam, R. D. 1993. Making democracy work.Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Woolcock, M. and D. Narayan. 2000. Social capital: implications for development

theory, research and policy. World Bank Research Observer,15(2): 225–250.