Rev. Mar. Cost. ISSN 1659-455X. Vol. 6: 29-36, Diciembre 2014.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/revmar.6.2

First record of Adeonellopsis subsulcata (Smitt, 1873) (Bryozoa: Gymnolaemata) in Cuba

Primer registro de Adeonellopsis subsulcata (Smitt, 1873) (Bryozoa: Gymnolaemata) en Cuba

Armando Sosa-Yañez1, 2*, Leslie Hernández-Fernández3 & Yunier Olivera3

1 Posgrado en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología (ICML), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Circuito Universitario s/n, Deleg. Coyoacán, México, D.F., CP. 04510.

2 Laboratorio de Sistemática y Ecología de Equinodermos, ICML, UNAM. Circuito Universitario s/n, Deleg. Coyoacán, México, D.F., CP. 04510.

3 Centro de Investigaciones de Ecosistemas Costeros (CIEC), Cayo Coco, Ciego de Ávila, Cuba.

*biol.armandsosa@gmail.com, leslie@ciec.fica.inf.cu, yunier@ciec.fica.inf.cu

Recibido: 10 de marzo de 2014

Corregido: 5 de mayo de 2014

Aceptado: 27 de mayo de 2014

ABSTRACT

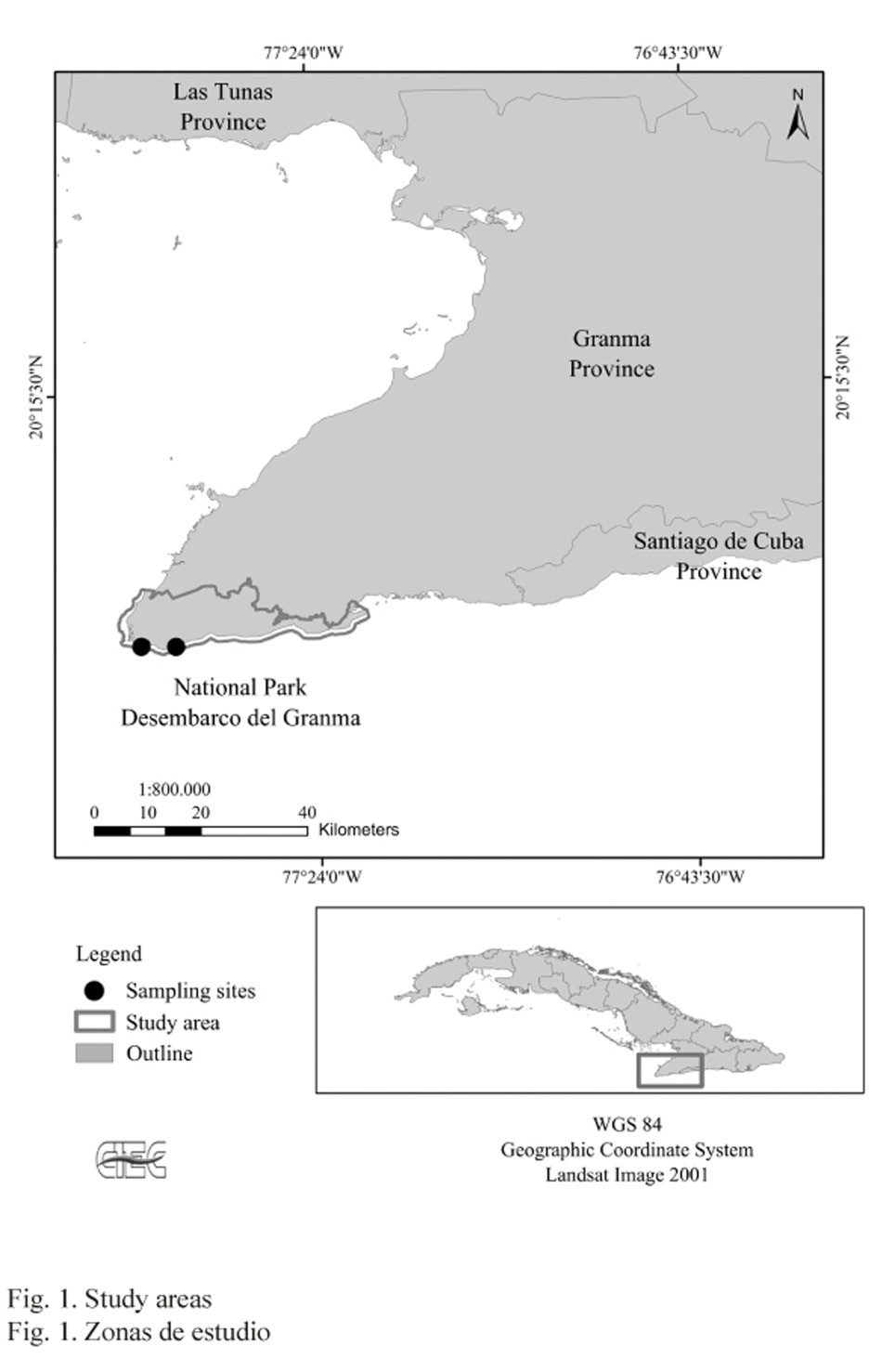

Adeonellopsis subsulcata (Smitt, 1873) (Bryozoa: Gymnolaemata) was first reported in Cuba on the marine terraces of the “Desembarco del Granma” National Park at the southeastern Cuban coast. Samples were collected using SCUBA gear at 12 m (19º 49’ 48’’ N, 77º 39’ 11’’ W) and 14 m deep (19º 50’ 04’’ N, 77º 42’ 34’’ W). Reference material has been included in the zoological collections of the Cuban Center for Coastal Ecosystems Research (Centro de Investigaciones de Ecosistemas Costeros-CIEC).

Keywords: First record, Bryozoa, Adeonidae, Adeonellopsis subsulcata, Cuba.

RESUMEN

Se registra por primera vez Adeonellopsis subsulcata (Bryozoa: Gymnolaemata) en las terrazas marinas del Parque Nacional “Desembarco del Granma”, costa suroriental de Cuba. Las muestras fueron recolectadas mediante buceo SCUBA a profundidades de 12 m (19º 49’ 48” N, 77º 39’ 11” W) y 14 m (19º 50’ 04” N, 77º 42’ 34” W). El material de referencia se encuentra depositado en las colecciones zoológicas del Centro de Investigaciones de Ecosistemas Costeros (CIEC) de Cuba.

Palabras claves: Primer registro, Bryozoa, Adeonidae, Adeonellopsis subsulcata, Cuba.

INTRODUCTION

Bryozoa is a phylum which comprises sessile, colonial suspension-feeders inhabiting both marine and freshwater environments throughout the world with nearly 5,900 living species (Appeltans et al. 2012) and 15,000 fossil species described (Vieira et al. 2008). Bryozoans are considered as one of the most abundant marine fouling organisms worldwide, yet their distribution has been poorly studied due probably to the fact they have been historically seen as uncharismatic microscopic animals with an unresolved and complex taxonomy (Tilbrook, 2012). Nevertheless, research on this phylum has experienced a remarkable increase during the last few decades, given its importance as a tool for describing paleo-ecological processes such as radiation (e.g. Jablonski et al. 1997) and major paleo-climatic events. In addition, bryozoans appear to be a critical component of ecosystems by increasing their habitat diversity and being part of food webs along a broad range of depths. More recently, some authors (e.g. Smith & Key, 2004; Saderne & Wahl, 2012) have identified them as indicators of possible effects of climate change and ocean acidification processes.

Marine bryozoans are abundant in Cuba, appearing in most of the marine ecosystems of the Cuban shelf. Although bryozoans are distributed in almost all the seas of the world, they are very commonly found in different biotopes, going from shallow to deep and away from the coast (Capetillo-Piñar, 2011). A huge gap of knowledge about their taxonomy and distribution still reigns in Cuban research. Most of the contributions are mere isolated anecdotal records that have described them as accompanying species to corals or marine vegetation. In Cuba, this phylum is represented by 84 species grouped into 2 classes and 37 families, being Stenolaemata the least diverse class including only 4 families and equal number of species (Capetillo-Piñar, 2007).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

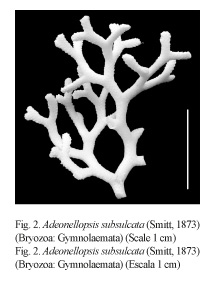

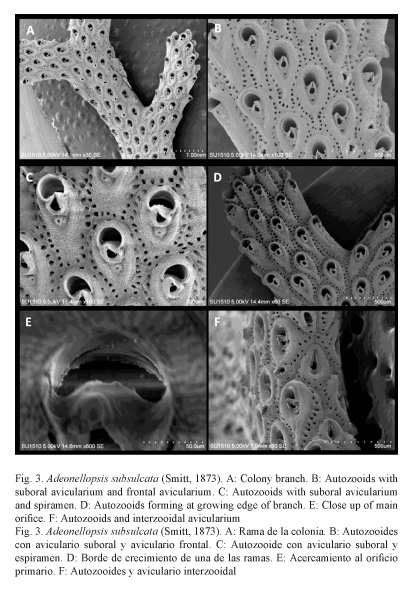

Samples were taken using SCUBA gear at 12 m (19º 49’ 48’’ N, 77º 39’ 11’’ W), and 14 m deep (19º 50’ 04’’ N, 77º 42’ 34’’ W) (Fig. 1) and mounted on stubs and coated with gold for observation with scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi S-2460N). Samples were measured with the Image J program, and then identified and taxonomically classified following the criteria described by Winston (2005) and Cheetham et al. (2007). Materials examined (CIEC 02.01. Figs. 2 and 3) were included in the zoological collections of the Center for Coastal Ecosystems Research (Centro de Investigaciones de Ecosistemas Costeros). Materials examined CIEC 02.01 (Fig. 2 and 3).

RESULTS

Systematics

Bryozoa Ehrenberg, 1831

Gymnolaemata Allman, 1856

Cheilostomatida Busk, 1852

Neocheilostomatina d’Hondt, 1985

Adeonoidea Busk, 1884

Adeonidae Busk, 1884

Adeonellopsis MacGillivray, 1886

Adeonellopsis subsulcata (Smitt, 1873)

Porina subsulcata Smitt, 1873, p. 28, pl. 6, figs. 136-140.

Adeonelladistoma var. imperforata Busk, 1884, p. 188, pl. 20, fig. 4.

Bracebridgia subsulcata (Smitt, 1873). Osburn, 1914, p. 199; 1940, p. 146; Canu & Bassler, 1928, p. 127, pl. 23, figs. 1-3; Maturo & Schopf, 1968, p. 277; Cook, 1973, p. 253, pl. 2, figs. 4-6; Cheetham et al. 1980, p. 350, 351; 1981, p. 71; Cheetham & Thomsen, 1981, p. 181; Lidgard, 1996, p. 173, fig. 5a, b; Cheetham et al. 1999, p. 188; Winston, 2005, p. 44, figs. 113-120.

Adeonellopsis subsulcata (Smitt, 1873), Cheetham, et al. 2007, p. 79, figs. 2.1, 2.2, 36.

Diagnosis: (modified from Cheetham et al. 2007). Autozooids approximately 60% longer than wider, with single orifice; while orifice and suboral avicularium still remain functional in growing zooids and younger zooids the spiramen disappears; frontal shield without tubercles; suboral avicularium with rostrum only slightly attenuated but distinctly projecting over proximal margin of secondary orifice; frontal avicularia slightly smaller than suboral avicularia and with more rounded rostrum, remaining functional after closure of orifice, spiramen, and suboral avicularium; interzooidal avicularia slightly larger than suboral avicularia.

Description: Bilaminate colony, erect from an encrusting base, composed of broad, flattened, and dichotomously branching fronds with five to seven rows of autozooids on each side, yellowish to pink. Zooids claviform, the frontal shield with very finely granular surface and imperforate except for spiramen, and rows of small marginal areolae and avicularian pores. The frontal surface convex at the margins and depressed at its center around the distally oriented spear shaped suboral avicularium. Single spiramen very small, as a subcircular pore that disappears early in ontogeny while orifice and suboral avicularium remain functional; with a slight collar when first formed. Small Areolae, separated by narrow interareolar buttresses at the earliest stages, distributed in one complete row around periphery; other frontal pores absent. Primary orifice slightly tilted distally, nearly semicircular, with strongly convex, finely serrated proximal margin. Secondary orifice strongly concave proximal margin indented by rostrum of suboral avicularium. Adventitious avicularia present suboral and rarely frontal avicularia. Suboral avicularium present on each autozooid, extending directly or slightly obliquely from a point just distal to the spiramen to the middle or toward one side of the proximal lip of the secondary orifice.

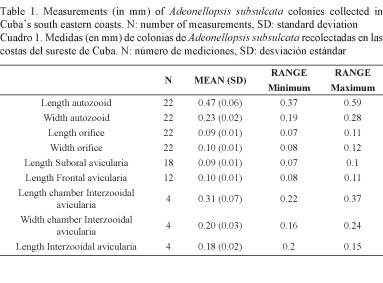

Single frontal avicularium, similar in form to suboral avicularium, but with more rounded mandibular portion and directed obliquely proximally or rarely transversely or obliquely distally, not present in all zooids. Interzooidal avicularia limited to lateral margins of branches, occurring at most contacts between autozooids of the two layers; avicularian chamber rhombic in outline, averaging approximately 50% as long and 60% as wide as autozooids longer than suboral avicularium, with more attenuated rostrum directed perpendicularly (Table 1); frontal surface similar to that of autozooid. No ovicells; embryos are brooded in gonozooids.

DISCUSSION

Adeonellopsis subsulcata was found inside reef formations dominated by stony coral colonies of Agaricia tenuifolia (Dana, 1846) and Montastraea annularis (Ellis & Solander, 1786) at 12 and 14 m deep. This is the first record of A. subsulcata for the coast of Cuba and the first record for this depth expanding their bathymetric range to shallower areas than reported in previous studies (Cheetham et al. 2007). South eastern Cuban coasts are characterized by a narrow marine terrace with strong water currents on account of its proximity to the Cayman Trench. Therefore, the present findings of A. subsulcata at the aforementioned depths could be explained because colonies are capable of withstanding stronger hydrodynamic conditions. The size of autozooids with frontal avicularia and suboral avicularia for the locations studied are lower than those reported; however, interzooidal avicularia are slightly larger. Adeonellopsis has been confused with Bracebridgia, MacGillivray, 1886, in having the colony rigidly erect or rarely encrusting, zooids claviform (Winston, 2005), frontal shields of autozooids imperforate except for areolae extending entirely around periphery, primary orifice more or less semicircular, secondary orifice similar in shape, avicularia adventitious and commonly vicarious or interzooidal (Cheetham et al. 2007). The main difference between the genera Bracebridgia and Adeonellopsis is the presence of a spiramen, not seen in Bracebridgia but easily observed in the early ontongeny of Adeonellopsis (Cook, 1973; Lidgard, 1996). The genus Bracebridgia was established for Mucronella pyriformis by Busk, 1884 who described this species without a spiramen; however, it has a primary orifice with a wide rounded internal denticle (lyrule) and lacks frontal avicularia (adventitious avicularia). Adeonellopsis subsulcata occurrence has been reported in Cape Hatteras, Bermuda, Florida, Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, 12-262 m (Winston, 2005), on epibenthic encrusting environments (Cheetham et al. 2007).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the personnel from the National Center for Protected Areas (Centro Nacional de Áreas Protegidas) and the GEF/UNDP project “Application of a Regional Approach to the Management of Marine and Coastal Protected Areas in Cuba’s Southern Archipelagos” (GEF Project ID: 3607) for providing the financial and logistical support. We are also grateful to Noel López who assisted us in the field, Stephen D. Cairns (Smithsonian Institution) for helping in the identification of the bryozoan colonies, M.C. María Berenit Mendoza Garfias (Institute of Biology-Instituto de Biología, UNAM) for helping us in taking the SEM photographs, Leandro M. Vieira (Centro de Biologia Marinha-CEBIMar from Universidade de São Paulo (USP) for the early review of this species, and the Graduate Program in Marine Sciences and Limnology (Posgrado en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología), UNAM.

First record of Adeonellopsis subsulcata (Smitt, 1873) (Bryozoa: Gymnolaemata) in Cuba por Revista Ciencias Marinas y Costeras se distribuye bajo una Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Costa Rica License.

Basada en una obra en http://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/revmar.

Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden encontrarse en revmar@una.cr.

REFERENCES

Busk, G. (1884). Report on the Polyzoa collected by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-1876. Part 1. The Cheilostomata. Rep. S. Res. H.M.S. Zoology., 10, 1-216.

Canu, F. & Bassler, R. S. (1928). Fossil and recent Bryozoa of the Gulf of Mexico region. Proc. Natl. Museum, 72, 1-199. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5479/si.00963801.72-2710.1

Capetillo-Piñar, N. (2011). Phylum Bryozoa (Polizoos, Ectoproctos o Lofoforados). In N. Capetillo-Piñar (Ed.), Los maravillosos Briozoos (pp. 3-5). Havana, Cuba: Boletín El Bohío.

Cheetham, A. H., Hayek, L.-A. C. & Thomsen, E. (1980). Branching structure in arborescent animals: models of relative growth. J. Theor. Biol., 85(2), 335-369. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(80)90025-9

Cheetham, A. H., Jackson, J. B. C., Sanner, J. & Ventocilla, Y. (1999). Neogene cheilostome Bryozoa of Tropical America: comparison and contrast between the Central American isthmus (Panama, Costa Rica) and the north-central Caribbean (Dominican Republic). In L. S. Collins & A. G. Coates (Eds.), A Paleobiotic Survey of Caribbean faunas from the Neogene of the Isthmus of Panama (pp. 159-192). Cambridge, USA.; Am. Paleontol.

Cheetham, A. H., Sanner, J. & Jackson, J. B. C. (2007). Metrarabdotos and related genera (Bryozoa: Cheilostomata) in the late Paleogene and Neogene of Tropical America. J. Paleontol., 81(Supplement), 1-96. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1666/0022-3360(2007)81[1:MARGBC]2.0.CO;2

Cook, P. L. (1973). Preliminary notes on the ontogeny of the frontal body wall in the Adeonidae and Adeonellidae (Bryozoa, Cheilostomata). Bol. Brit. Mus. (Nat. Hist.), Zoology, 25(6), 243-263.

Jablonski, D., Lidgard, S. & Taylor, P. D. (1997). Comparative ecology of bryozoan radiations: Origin of novelties in Cyclostomes and Cheilostomes. Palaios., 12, 505-523. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3515408

Maturo, F. J. S. & Schopf, T. J. M. (1968). Ectoproct and entoproct type material: re-examination of species from Bermuda and New England collected by A. E. Verrill, J. W. Dawson & E. Desor. Postilla, 120, 1-95.

Osburn, R. C. (1914). The Bryozoa of the Tortugas Islands, Florida. Carnegie I. Wash. Pub., 182, 183-222.

Osburn, R. C. (1940). Bryozoa of Porto Rico: With a résumé of West Indian Bryozoan fauna. Sci. Surv. Porto Rico & Virgin Islands, 16, 321-486.

Saderne, V. & Wahl, M. (2012). Effect of ocean acidification on growth, calcification and recruitment of calcifying and non-calcifying epibionts of brown algae. Biogeosciences Discuss., 9, 3739-3766. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/bgd-9-3739-2012

Smith, A. M. & Key, M. M. Jr. (2004). Controls, variation, and a record of climate change in detailed stable isotope record in a single bryozoan skeleton. Quat. Res., 61(2), 123-133. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yqres.2003.11.001

Tilbrook, K. J. (2012). Bryozoa, Cheilostomata: First records of two invasive species in Australia and the northerly range extension for a third. Check List, 8(1), 181-183.

Vieira, L. M., Migotto, A. E. & Winston, J. E. (2008). Synopsis and annotated checklist of recent marine Bryozoa from Brazil. Zootaxa, 1810, 1-39.

Winston, J. E. (2005). Re-description and revision of Smitt’s “Floridan Bryozoa” in the collection of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University. Virginia Museum Nat. Hist. Mem, 7, 1-147.