Abstract

With respect to the premises of fair trade, its initiatives experienced a metamorphosis between the 1940s and late 1980s. Through the iconic dependency and “development of underdevelopment” schools of thought, the evolution of the development theory has shaped fair trade premises and principles. Despite the fact that these schools of thought contended the premises of neoliberal markets, their intention to change the world trading system and its unequal exchange was the result of a limited application of social relations of production rather than economic exchange relations. These factors, in addition to the declining role of the State in development during the late 1980s, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the counter-revolution of neoliberalism in the early 1990s, led to the redirection of the focus of fair trade initiatives.

The resurgence of neoliberal market forces starting in the 1990s led the fair trade network (what was left of the fair trade movement born in the 1940s) to implement market-friendly strategies to better position themselves in the international mainstream market. Despite the fact that the neoliberal counter-revolution led to the revival of the fair trade network, this does not mean that the network lost its original premises of fair prices and fair exchange or its loyalty to its Southern partners. Its new reality is promising, but its new “dependency” on market-friendly approaches could also continue to shape its raison d’être.

Keywords: Development; Dependency; Theories; Fair Trade; Costa Rica; Coffee.

Resumen

Con respecto de sus fundamentos, las iniciativas del comercio justo experimentaron una metamorfosis entre la década de 1940 y finales de la década de 1980. A través de las escuelas de pensamiento icónicas de la dependencia y del “desarrollo del subdesarrollo”, la evolución de la teoría del desarrollo ha formado los principios y supuestos del comercio justo. A pesar de que estas escuelas de pensamiento cuestionan los supuestos de los mercados neoliberales, su intención de cambiar el sistema de comercio mundial y su intercambio desigual fue el resultado de una aplicación limitada de las relaciones sociales de producción en lugar de las relaciones económicas de intercambio. Estos factores, además del papel declinante del Estado en el desarrollo a finales de la década de 1980, el colapso de la Unión Soviética, y la contrarrevolución neoliberal a inicios de la década de 1990, llevaron al movimiento del comercio justo a redireccionar su enfoque.

El resurgimiento de las fuerzas neoliberales a inicios de la década de 1990, llevó a la red del comercio justo (lo que quedó del movimiento originado en la década de 1940) a implementar estrategias amigables con la filosofía de mercado para posicionarse mejor dentro del mercado dominante internacionalmente. A pesar de que la revolución neoliberal llevó al renacimiento de la red de comercio justo, esto no significa que la red haya perdido su sentido original de precios justos e intercambio justo, o su lealtad a los países del Sur Global. Su nueva realidad es prometedora, pero su nueva “dependencia” en enfoques amigables con el mercado puede también moldear su raison d’être.

Palabras clave: Desarrollo; Dependencia; Teorías; Comercio justo; Costa Rica; Café.

Introduction

The fair trade (FT) movement, which originated in the Global South’s non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governments, and international organizations, is an alternative and parallel initiative that seeks to adjust the world trading system and international development scheme for the benefit of smallholders. Its primary aim is to eliminate “unfair” trade practices and “unequal” exchanges, as well as to establish international cooperative mechanisms to regulate the market economy and achieve “fair” prices and labor conditions. Between the 1940s and the 1980s, the movement expanded significantly due to the influence of “embedded liberalism”, which is understood as a post Second World War framework. According to Ruggie (1982), the movement’s main objective is explained as follows: “unlike the economic nationalism of the thirties, it would be multilateral in character; unlike the liberalism of the gold standard and free trade, its multilateralism would be predicated upon domestic interventionism” (p. 393). Its expected effect in the international economic system was to prevent crises.

However, by the late 1980s, the values that supported the movement’s premises and initiatives started to face rejection, and the movement began to experience a decline in the early 1990s when neoliberal globalization returned to the stage. By the early 1990s, it began to shift its focus from the ideas of “unfair” product prices and getting “trade not aid” (IFAT in Renard 2003, p. 89) to the need for a regulatory state that could support its principles. Market-friendly goals were applied as of the 1990s by drawing closer to mainstream neoliberal markets and to multinational corporations. Ever since, the network’s sales have flourished, and FT has been thriving in the times of market neoliberalism.

Thesis statement: As development theories have evolved, influenced by macro-structures of power and their historical, social, and political-economic roots, the premises of fair trade have also adapted to changing market circumstances.

The main objectives are the following: 1. Develop a literary review of the most influential underdevelopment and dependency theories, in order to determine the manner in which they shaped the fundamentals of the FT movement between the 1940s and the 1980s; 2. Examine the factors that fostered the FT movement’s shift from its original objectives towards a more market-friendly neoliberal approach in the late 1980s; 3. Conduct a comparative analysis of underdevelopment, dependency, and neoliberal theories with the FT and the fair trade network; 4. Analyze how international coffee prices and certified Fairtrade coffee prices have evolved recently as a means to understand how neoliberal globalization could be counterbalanced by the Fairtrade certification scheme.

1.Methods

In order to answer the research statement, as well as achieving the established objectives for this study, the following research methods have been applied.

A descriptive literature review is conducted in order to determine whether a series of theories and concepts in a specific research topic unveil “any interpretable pattern or trend with respect to pre-existing propositions, theories, methodologies or findings” (Paré et al., 2015, p. 186). The heterodox development theory is also assessed in order to determine the possible influence it may have had on the premise and fundamentals of the FT movement as well as its network’s premise.

A historical materialist methodology approach is applied in order to identify macro-structures of power and their historical, social, and political-economic roots. Specific historical modes of production are crucial to determining the distribution of political-economic power and socially produced wealth in society. This methodology also allows for determining the manner in which different development theories and their macro-structures are shaped by the various modes of production, and how they may have influenced the premise of the FT movement and its network.

2.Theoretical foundations and their connection to fair trade

The heterodox development theory and its influence on the fair trade movement

After World War II, development was analyzed mainly through conventional orthodox models, which used the European path as benchmark. Therefore, any other development model that did not follow this path -modernization, industrial growth, economic growth, etc.-, was not development. This is also known as Eurocentricity as proposed by Samir Amin (1974).

However, disillusion with orthodox development theories became evident in the 1960s due the use of the development concept as an ideological weapon during the Cold War as well as increasing international and national poverty and inequality gaps. This led Paul Baran (1957) and Cardoso and Faletto (1979) to analyze the international economic system from a Marxist perspective, in which an economic surplus (Baran, 1957, p. 21) originated from the exploitation and domination of rich capitalist nations of the core on the “backward” less developed nations of the periphery. Such critique created a rupture with conventional development models. This is how the heterodox theories of development started and how an opportunity emerged for a new critical alternative to the mainstream beliefs: the FT movement. Does the FT movement evolve as development theory develops?

Heterodox economists believe that very profound changes must occur in the Global South for development to take place (Cypher, J. and Dietz, J., 1997, p. 178). From the perspective of this essay, heterodoxy is subject to the analysis of the dependency theory, which includes the three most important schools of thought: structuralism (Prebisch, 1950), the Marxist dependency theory (Baran, 1957), and the associated non-Marxist dependency theory (Cardoso, 1972). Each school is discussed based on a historical materialist approach, while the alternative market proposed by fair traders is addressed from a comparative perspective.

Structuralism is a very influential heterodox theory, whose key pillar is its criticism of mainstream international trade based on comparative advantage. The most important advocate of structuralism in Latin America was Raul Prebisch (1950), who, beginning in the 1920s, studied the theory based on the experience of Argentina, which was a successful example of trade openness and specialization. The Latin American country’s export-led growth focused on a few primary commodities that drove its overall successful development. However, Argentina’s success story took an important turn during the late 1920s and 1930s as export prices with its primary industrial trade partner, England, began to fall. Argentina was also strongly impacted by the Great Depression as well as the growing power of the hegemonic United States in the global economy. These effects continued to be felt over the following decades, further worsening Argentina’s and peripheral countries economic development and trade balance, especially when compared to the late 1890s and early 1900s.

Prebisch’s argument was based on a United Nations (1949) study entitled Relative Prices of Exports and Imports of Underdeveloped Countries, which reveals that the ratio of prices of primary commodities to those of manufactured goods analyzed moved from .100 during the 1876-1880 period to .68 during the 1931-1935 period (Prebisch, 1950, p. 8). In Prebisch’s (1950) own words: “The enormous benefits that derive from increased productivity have not reached the periphery in a measure comparable to that obtained by the peoples of the great industrial countries” (p. 1).

Considering possible policy solutions to counterbalance the weakening trade balance of countries in the Global South, Prebisch (1950) advocated for ‘development from within’, also known as Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI). Along similar lines, Cypher and Dietz (1997) analyzed some of the most important arguments in favor of industrialization in the Global South: a. in order to change the export production structure, the Global South nation could adopt a development strategy such as the productive structure of the Global North; b. if more industrialization took place, more economic success could be obtained; and c. technological spillovers in agriculture could lead to greater productivity and a larger manufacturing base.

Together with Raul Prebisch, Hans Singer proposed the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis, (Prebisch, 1950; Singer, 1950; Singer, 1984) according to which the Global North could benefit from international trade and economic transactions by taking advantage of the Global South. Such relationships could lead Northern countries to obtain higher levels of development at a high cost for the Global South. Technological advances in traded goods could also increase workers’ productivity and wages. As a result, the center nations would be able to buy the periphery’s cheaper imported primary products using the profit obtained from their manufacturing exports, while providing workers with higher wages. On the other hand, periphery nations would lower export prices due to new technology, forcing them to export more products in order to be able to purchase the same quantity of manufactured products from the center (Cypher, J. and Dietz, J., 1997, p. 178).

The evolution of the FT movement, its principles and premises, may have been shaped by the influence of structuralist theory as stated in this study’s thesis statement. Such analysis is included in a later section of this study.

With respect to the Marxist dependency theory, it is important to highlight the ideas considered as premises by this school of thought. Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy (Baran and Sweezy, 1966), the theory’s primary advocates, considered that monopoly capitalism had an antagonistic effect since it sought to preserve backwardness and a dependence on the Global South.

Baran’s argument revolved around the concept of economic surplus. The Global North had focused on extracting surplus from the Global South. Baran (1957) studied the history of colonialism in great detail and determined that it blocked the potential for change. He concluded that “the peoples who came into the orbit of Western capitalist expansion found themselves in the twilight of feudalism and capitalism, enduring the worst features of both worlds” (Baran, 1957, p. 144). Although the surplus extracted from the South afforded an opportunity for reinvestment in productive uses, it was misused. The stagnation and backwardness of less-developed regions was a result of the surplus being sent to the North. If the Global North had invested more in the Global South, its level of development today would likely be better.

He emphasized the elements that could propel economic development through economic surplus in less-developed regions: national capital, foreign investment and the State. Based on the ideas championed by Prebisch and Singer (Prebisch, 1950; Singer, 1950; Singer, 1984), Baran considered that some less-developed regions could benefit from ISI and transform their productive structure. However, Baran also stated that the presence of unscrupulous monopolies and oligopolies could result in a national economy that was neither functional nor articulated. Moreover, foreign investment faced limitations in achieving development in less-developed regions.

According to Baran (1957), the purported advantages of the international trading system and international capital were only enjoyed by a few exporting enclaves, such as staple crops and mining, within the national economic system. Generally, the enclaves were owned and controlled by foreign enterprises. He stated that “the principal impact of foreign enterprise on the development of the underdeveloped countries lies in hardening and strengthening the sway of merchant capitalism, in slowing down and indeed preventing its transformation into industrial capitalism” (Baran, 1957, p. 194).

However, the State in the foreign investment recipient countries could also break the deadlock on unequal exchange by implementing new programs which could make “development from within” more dynamic and prosperous. Overall, Baran argues that “the development of a socialist planned economy is an essential, indeed indispensable, condition for the attainment of economy and social progress in underdeveloped countries” (Baran, 1957, p. 261). To what extent did Marxist dependency theory penetrate in the FT movement’s beliefs and premises? This is analyzed in a later section of this study.

Another noteworthy dependency theory is associated dependent development, known as the non-Marxist dependency theory. The most important intellectual advocate of associated dependent development was Fernando Cardoso (Cardoso and Faletto, 1979). He had an optimistic perspective regarding the progress of Global South countries given that they had continued their development and, consequently, this trend could continue.

To support this argument, Cardoso developed a 3-phase development route for Global South regions. First, colonial times were characterized by a dual rural-urban economy in which the agricultural sector attempted to export to the international market. The most relevant part of the economic activity was carried out at the artisanal level, involving peasants and petty producers. Moreover, other modern semi-capitalist sectors of the local economy were integrated into the global economy. Secondly, a “developmentalist alliance” (Cypher, J. and Dietz, J., 1997, p. 193) evolved around ISI, which led to a new social structure of accumulation involving industrial workers, merchant capitalists, governmental employees and other economically buoyant individuals in society. It resulted in the transition from an agro-export economy to ISI. Thirdly, an authoritarian-corporativist regime replaced the ISI strategy of development.

The weakening of states during the ISI period led to a loss of influence with respect to public spending in society. This, in turn, afforded an opportunity for multinational corporations to settle in the Global South (Cypher, J. and Dietz, J., 1997, p. 193). Multinational companies became key players in society as catalysts of change in the various economic sectors and played a fundamental role in the achievement of higher development stages by the Global South. Did the associated dependent development theory permeate the original FT movement’s beliefs and premises? Has the FT movement been influenced by the development of development theory? The next section makes a comparative analysis to approach these questions.

Relation between dependency and underdevelopment theories and the evolution of the fair trade movement (Phase 1:1940s-1980s)

The period from 1940 to 1980 represents the origin of what is known as the modern FT movement. During this period, FT initiatives focused on achieving two relevant outcomes: a. reducing trade barriers in the Global North, given that, according to fair traders, they prevented smallholders from developing value-added production (Barratt Brown, 1993, p. 92); b. establishing an international cooperative system to regulate the world market through a statist approach.

The structuralist arguments developed by Prebisch and Singer (Prebisch, 1950; Singer, 1950; Singer, 1984) viewed trade as a tool that served the interests of the Global North, which could reap the benefits of product exchange and investment. The disillusion experienced by development theorists with respect to unequal terms of trade in the Global South was associated with the Ricardian model of comparative advantage. This channeled the discussion towards the creation of alternative trade markets, which could contest the premise of neoliberal trade theories.

The structuralist objective to reduce unequal terms of trade and transform the center-periphery relationship for the benefit of poor farmers in the Global South, by means of an alternative world trading system, required the support of strong international regulations. The statist emphasis of this theory was relevant, given that capitalist market development considered that exchange relations were privileged compared to social production relations. According to structuralists, North-South terms of trade were unequal; therefore, they envisaged a policy solution based on the idea of ISI as well as market regulations to support development efforts in the Global South.

The origins of alternative trade and parallel markets can be traced back to NGOs in the Global North in the 1940s, which imported products from smallholders in the Global South (Redfern and Snedker, 2002, p. 5), as well as in Europe in the 1950s (Giovannucci and Koekoek, 2003, p. 38). By 1964, this alternative form of trade became more organized in the form of Alternative Trade Organizations (ATOs), the first of which was founded by Oxfam UK. ATOs shifted the premise of alternative trade, emphasizing trade reform as an engine for development under the motto “trade not aid” (Renard, 2003, p. 89). Through this re-expressed alternative value chain, ATOs could push for improved distribution of income and fairer terms of trade. As indicated by the International Federation of Alternative Trade (IFAT) (currently known as the World Fair Trade Organization), “alternative trade operates under a different set of values and objectives than traditional trade, putting people and their well-being and preservation of the natural environment before the pursuit of profit” (IFAT in Renard 2003: p. 89).

As part of the dependency theory, the Marxist dependency school of thought made a very important and radical contribution to the development of FT as an alternative market. Paul Baran (1957) was a radical thinker who opposed the world’s capitalist system and asserted that it was useless in facilitating developmental benefits for the Global South and its inhabitants. His approach toward FT aimed to promote radical reforms to the existing trade system, while also seeking to lay the foundation for an alternative trade system that could provide new opportunities for the Global South and their products.

Marxist dependency theorists focused on combating unfair commodity prices, achieving “trade not aid” and fostering national and international market regulation to support its efforts. Moreover, Paul Baran developed a critique that stated that the outcome of world capitalism was reflected in unequal exchange; therefore, he proposed the idea of a new economic order. These ideas permeated deeply among fair traders in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. (Baran and Sweezy, 1966).

Baran’s school of thought, though radical, did not prevail. Despite its sound argument and the support that it received from important development circles, the deeply embedded liberal framework allowed for a degree of restrictive practices to maintain the stability of the world trading system (Helleiner, 1994), with support from international commodity control schemes such as those of the 1948 Havana Charter, as well as the interventional use of buffer stocks and compensatory funds for some commodities. Northern countries also firmly opposed providing the conditions for the trading system to undergo a radical change. Consequently, the mechanisms promoted by embedded capitalism did not set adequate conditions for the Marxist dependency theory to become a reality.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in 1964 and 1976 was an opportunity for fair traders to push forward their agenda, which proposed an Integrated Program for Commodities. The program consisted of international commodity stocks to control price fluctuations, funding from a common pool of resources, a compensatory finance mechanism for primary commodities, and the elimination of unfair Global North protectionist barriers. The single aspect that was able to withstand the pressure from the Global North was the idea to develop common funds to provide financial support for producers in the Global South.

Associated dependent development, also known as the neo-structuralist school of thought, was very critical of the world trading system, in which unequal exchange was permitted. However, Cardoso shared his perspective on multinational corporations (MNCs), thereby playing a key role in finding a pathway to development (Cardoso and Faletto, 1979). Through his stages of development approach à la Rostow, Cardoso developed a scenario in which certain economic sectors of the Global South could develop promising linkages that could not only push ISI, but also take development to a higher level. The decline of embedded capitalism and the establishment of an authoritarian-corporativist regime provide an important argument in favor of the emergence of MNCs.

Local elites could also play a very relevant role in setting the stage for changes that could propel development in the Global South. Cardoso developed and supported the Prebisch-Singer argument that surplus extracted primarily for the Global North’s advantage was detrimental to the Global South. He also described the key role that local elites could play in the local economy while pursuing more favorable terms of trade.

Despite the possibility of the State losing some of its influence during the third phase of an authoritarian-corporativist regime, it could play a relevant role in the distributional effect of the wealth generated by MNCs. Either through new development programs, a fair distribution of wealth, or a progressive corporate taxation system, the State could promote development.

Another prominent theory that focuses on a historical materialistic analysis and is critical of the unequal exchange between the Global North and the Global South, as well as the extraction of economic surplus for the benefit of the center is “development of underdevelopment” (Frank, 1969, p. 3).

Despite the general notion that the Global South’s history, as well as its present, simulates the historical path of the Global North today, recent research has demonstrated that “contemporary underdevelopment is in large part the historical product of past and continuing economic and other relations between the satellite underdeveloped and the now developed metropolitan countries” (Frank, 1969, p. 4). Therefore, instead of merely analyzing the Global South’s stages of economic development, Frank (1969) underscored the relevance of “the economic, political, social, and cultural relations” that emerge and develop “as a result of the development of the capitalist system” (Frank, 1969, p. 4). The potential impact of North-South relations on international trade, trade agreements, and the development agenda shape important exchange relations that could eventually determine the amount of economic surplus derived from these exchange relations. Trade and economic relations play a crucial role in bringing forth the modern capitalist system, but exchange relations are also critical in the analysis of the ways in which the national metropoles of the Global South are intertwined with the metropoles of the developed North (Frank, 1969, p. 4).

Frank stated that “each of the satellites… serves as an instrument to suck capital or economic surplus out of its own satellites and to channel part of this surplus to the world metropolis of which all are satellites” (Frank, 1969, p. 6). The metropoles of the Global North receive the economic surplus extracted from the metropoles of the Global South. They themselves are the satellites of the Global North with their powerful metropoles. However, the metropoles of the Global South, though producers, also receive the surplus produced in other satellite cities or productive agricultural areas within the Global South region. The economic surplus would accumulate in these metropoles of a colonial background, which would, in turn, transfer this accumulation of surplus to the powerful metropoles of the Global North.

According to Frank (p. 5),

“the economic, political, social, and cultural institutions and relations we now observe are the products of the historical development of the capitalist system no less than are the seemingly more modern or capitalist features of the national metropoles of these underdeveloped countries.”

This led Frank (1969) to argue that the “present underdevelopment of Latin America is the result of its centuries-long participation in the process of world capitalist development” (Frank, 1969, p. 6).

The FT movement tends to degrade the fundamentals of the capitalist market, by considering that they are primarily the result of commercial exchanges rather than a social exchange. Moreover, the FT movement does not radically challenge the social relations of production behind the market economy imperatives of competition, accumulation and profit making. Instead, exploitation is viewed as the result of actions by immoral market actors (Fridell, 2007).

During this period, fair traders had two primary demands: a. to eliminate “unfair” trade practices and “unequal” exchange, and b. to establish international cooperative mechanisms to regulate the world market and achieve “fair” prices and labor conditions for small-scale commodity producers and workers in the Global South (Fridell, 2007). The FT movement experienced a rude awakening during the 1970s and 1980s in particular. The powerful Global North and their monopolistic and oligopolistic trading power and macro structures presented a strong opposition to the above-mentioned demands; this has been politically criticized by international forums and organizations such as UNCTAD. On the other hand, the weakening of embedded capitalism by the late 1980s, the Soviet Union’s political and economic debacle in the early 1990s, as well as the failure of commodity agreements, put the FT movement in a very fragile and weak position.

Fair traders began to confront these constraints head-on and to consider that NGOs, rather than the State, represented the primary means for development. NGOs’ “role is generally viewed as subsidiary, not central, to the fair trade network” (VanderHoff Boersma 2001, p. 44). During this period, fair traders also shifted their focus from creating an alternative market to changing the world trading system. This set the stage for the rechanneling of FT objectives in the decades to come.

Resurgence of neoliberalism in the development theory and its influence on the fair trade network. A return to orthodoxy? (Phase 2: Late 1980s to present)

As the State lost predominance as a central development actor by the end of the 1980s, along with the weakening of the abovementioned dependency theories, the FT movement abandoned its original objective of implementing an alternative trade system, aiming instead to access mainstream capitalist markets. This would facilitate efforts aimed at meeting the needs of smallholders in the Global South.

“Over the past two decades, the fair trade vision has changed from an alternative trading network composed of Alternative Trading Organizations dealing exclusively in fair trade products, to a market niche driven by the interests of giant conventional corporations with minor commitments to fair trade given their overall size” (Fridell, 2007, p.6).

In order to achieve this objective, fair traders organized themselves in a network that promoted labelling initiatives, but they also “stepped up their efforts in consumer research, marketing strategies, and quality control” (Fridell, 2007 p. 45)

Additionally, the shift in the objectives of fair traders resulted from “the dramatically altered political-economic and ideological conditions ushered by the rise of neoliberal globalization” (Fridell, 2007, p. 45). Thanks to neoliberal reforms in the 1990s and the deterioration of the State’s influence at the global level, the political-economic realities under which the fair trade network had to operate changed significantly.

Forces more powerful than the fair trade network have proven capable of pulling the network away from its more radical vision influenced by the heterodox dependency and development of underdevelopment theories, towards one with an increasingly neoliberal essence. Such forces can be better depicted by studying the Fairtrade coffee market prices in its recent past.

3.Analysis of the evolution of Fairtrade coffee market: from 1990 to 2017

This shift in focus towards market-affirming fair trade initiatives extended the scope of the fair trade network, drawing closer to mainstream value chains during the 1990s. As a result, it had to satisfy the demands of corporate buyers, articulating an increasingly buyer-driven value chain. Despite the expansionary logic that has propelled fair trade’s mainstreaming efforts, the contradiction between criticizing conventional market forces and still relying on them is fundamentally problematic. For better or for worse, fair trade has moved away from its roots, and the division between “free” and “fair” trade is shifting.

In order to gain a better understanding of the manner in which market forces and globalization have rechanneled the premise of fair trade towards the neoliberal school of thought, a market price analysis was conducted as a means to understand the implications for the fair trade network.

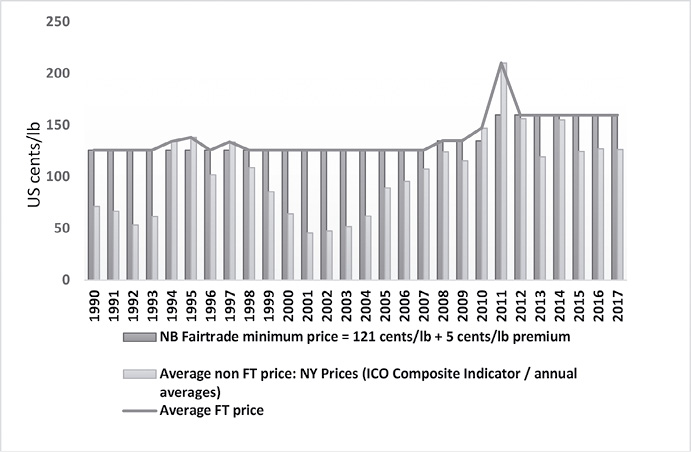

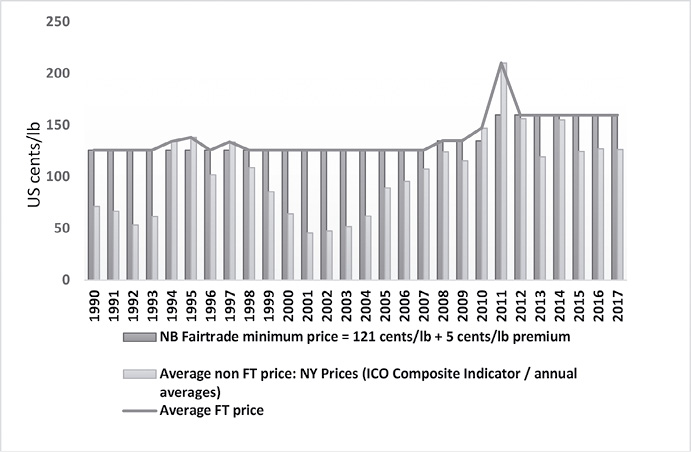

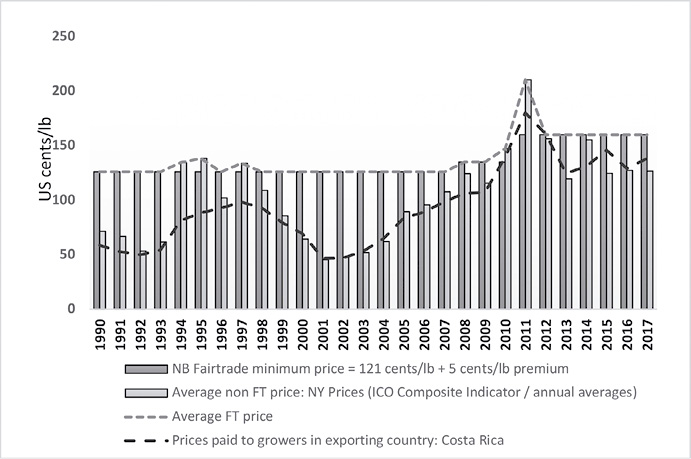

Following the collapse of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) in 1989, the New York coffee price, which is used as the international reference price, has experienced a very variable path over the past 27 years, as depicted in Graph 1. The price is determined based on the daily settlement price of the 2nd position Coffee C Futures contract at ICE Futures US for Arabica coffee (ICO, 2018).

Different phenomena such as the frost experienced by Brazil in 1994, as well as the 1997 and 1999 droughts, led to significant reductions in supply, which exerted growing pressure on the New York price. Afterwards, a global overproduction of coffee led the New York price to reach its lowest point in 30 years, even lower than production costs.

Graph 1: Coffee market (1990-2017): Comparison of NB Fairtrade minimum price, Average non FT price, and Average FT price

Source: FLO annual reports (2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017) and ICO (2018)

Subsequently, the recovery of prices lasted until the fall of 2008, when world commodity prices were affected by the global financial crisis. Thereafter, prices continued to exhibit an upward trend, which made the New York price reach a 30-year high in 2011. The global demand for coffee continued to increase during those years, and producers responded by continuously increasing their productive capacity (FLO, 2009).

At a certain point in 2011, the price surge reached an inflection point due to a surplus in production, which lasted until 2013. Producers continued to increase their capacity beyond what the market was able to absorb. Additionally, hot and dry weather in Brazil led to an additional downward pressure on prices. By 2014 and 2015, the entry of new and smaller coffee-producing countries into the world coffee market led to an increase in output and a recovery of the New York prices. Between 2016 and 2017, the New York price for Arabica coffee ranged between 124.67 and 127.31 cents per pound (FLO, 2016-2017).

How does the Fairtrade coffee initiative provide an alternative for Costa Rican smallholders to counterbalance volatility of New York prices? The following discussion provides a reasonable scenario to understand the possible benefits of Fairtrade coffee schemes for producing organizations and farmers.

Fairtrade average price and minimum price: a highly synchronized duet

As a result of the abovementioned volatility of New York Arabica prices, there is unequal bargaining power between producers and consumers (Reinecke, 2012, p. 567). This is one of the reasons why producers seek to obtain the Fairtrade certification.

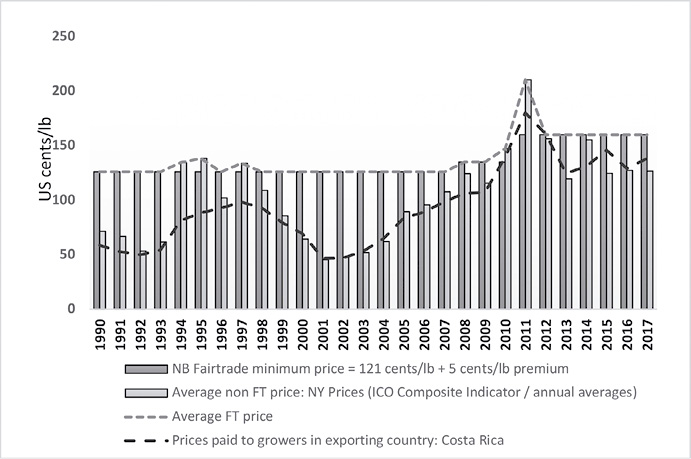

The goal of sustaining a minimum price floor system is to ensure that producers are able to cover the cost of their sustainable production (Reinecke, 2010, p. 571). It allows producers to receive a minimum revenue that cannot fall below what FLO considers to be the average cost incurred by farmers when world markets fall below a sustainable level. Has this minimum price floor system proven effective in preserving and protecting the revenues and sales of Fairtrade coffee smallholders in Costa Rica? Graph 2, which indicates the farmgate price paid to Costa Rican smallholders, sheds light on this question.

The Fairtrade minimum price is estimated by the Standards Unit at FLO. Fairtrade standards, in turn, are guided by the ISEAL Code of Good Practice for Social and Environmental Labelling (FLO, 2013/2014), in which producers, traders, social actors, and other relevant stakeholders participate in the research, consultation and final decision-making processes.

The Fairtrade average price tends to match the Fairtrade minimum price. However, the Fairtrade average price has a very distinguishing feature, given that, when the New York coffee price is higher than the Fairtrade minimum price, the buyer pays the higher price (Raynolds, 2000, p. 301). In this case, the higher price becomes the Fairtrade average price as well the temporary minimum price. This provides a degree of flexibility that is advantageous for producers and workers in certified organizations, given that they will always benefit from market conditions.

Graph 2 depicts the Arabica Coffee market from 1990 until 2017. The Fairtrade minimum price is compared to New York normal market prices. As indicated in Graph 2, the international market price has always been characterized by its high volatility (Lewin et al., 2004, p. 104), and the Fairtrade coffee minimum price and the Fairtrade coffee average price represent a very attractive safety net for Fairtrade coffee producers.

Overall, based on Graph 2, it is possible to deduce that producers without the benefit of the Fairtrade minimum price would be adversely impacted by decreases in the New York coffee price. Participation in fair trade networks helps to reduce the vulnerability of farmers’ livelihoods (Bacon, 2004, p. 498).

In a thought-provoking way, Graph 2 illustrates how the price paid to Costa Rican producers relates to the Fairtrade minimum price and the NY price. This corresponds to the average prices paid to growers in the exporting country (in this case, Costa Rica at the farmgate level), or the minimum price guaranteed by the government to growers, by form and weight reported in the national currency in which the coffee is purchased, and converted into U.S. cents per pound.

Graph 2: Coffee market: 1990-2017: Comparison of average Fairtrade price, NY prices, Fairtrade minimum prices, and prices paid to Costa Rican coffee growers

Source: FLO annual reports (2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017) and ICO (2018)

The price paid to Costa Rican coffee growers at the farmgate level has always been below the Fairtrade average and the Fairtrade minimum price during the period analyzed (1990 to 2017). Costa Rican traditional coffee producers have been vulnerable to the volatility of the New York price, as well as the adverse market conditions.

The consequences can be disastrous for Costa Rican coffee growers, especially during difficult periods such as in 2001, when the New York coffee price reached the lowest point in the period analyzed, dropping to .46 cents a pound.

Final remarks

With respect to their premise, fair trade initiatives experienced a metamorphosis between the 1940s and late 1980s. Through its iconic dependency and underdevelopment schools of thought, the development of an underdevelopment theory has shaped fair trade premises and principles. Despite the fact that these schools of thought contended the premise of neoliberal markets, their intention to change the world trading system and its unequal exchange was a result of the limited application of social relations of production instead of economic exchange relations. Additionally, there was a certain level of confrontation between fair traders and the conventional market forces represented in relevant development circles such as the UNCTAD conferences. These factors, in addition to the declining role of the State in development during the late 1980s, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the counter-revolution of neoliberalism in the early 1990s, led the fair trade initiatives to redirect their focus.

The resurgence of neoliberal market forces starting in the 1990s led the fair trade network to implement market-friendly strategies to better position themselves in the international mainstream market. For instance, fair trade average network’s price, as well as its minimum price, has provided smallholders with economic sustainability. New labelling initiatives and the market forces of globalization have provided the fair trade network with an opportunity to achieve economic sustainability as a result of this positive symbiotic relationship. Despite the fact that the neoliberal counter-revolution led to the revival of the fair trade network, this does not mean that the network lost its original premise of fair prices and fair exchange or its loyalty to its Southern partners. Its new reality is promising, but its new “dependency” on market-friendly approaches could also continue to shape its raison d’être.

References

Amin, S. (1974). Accumulation on a world scale: a critique of the theory of underdevelopment. Monthly Review Press, vol. 2. Retrieved from https://monthlyreview.org/product/accumulation_on_a_world_scale/

Bacon, C. (2004). Confronting the coffee crisis: can fair trade, organic and specialty coffees reduce small-scale farmer vulnerability in Northern Nicaragua? Science Direct, 33:497511.

Baran, P. (1957). The political economy of growth. United States: Monthly Review Press. New York: John Calder Publishers.

Baran, P. & Sweezy, P. (1966). Monopoly capital: an essay on the American economic and social order. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Barratt Brown, M. (1993). Fair trade: reform and realities in the international trading system. London, England: Zed Books.

Cardoso, F. (July- August 1972). Dependent capitalist development in Latin America, New Left Review. London. Retrieved from https://newleftreview.org/issues/I74

Cardoso, F. & Faletto, E. (1979). Dependency and development in Latin America. Los Angeles, United States: University of California Press.

Cypher, J. & Dietz, J. (1997). The Process of economic development. London, England: Routledge, p. 169-197.

Ehrlich, S. (2018). The Politics of fair trade: moving beyond free trade and protection. New York, United States: Oxford University Press.

Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International -FLO- (reports from 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013,2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017). The Benefits of Fairtrade: A Monitoring and Evaluation Report of Fairtrade Certified Producer Organisations for 2008 (2nd ed.). Bonn, Germany. Retrieved from https://monitoringreport2016.fairtrade.net/en/

Frank, A. G. (1969). Latin America: underdevelopment or revolution. Essays on the development of underdevelopment and the immediate enemy. New York, United States: Monthly Review Press.

Fridell, G. (2007). Fair trade coffee: The prospects and pitfalls of market-driven social justice. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Giovannucci, D. & Koekoek, F. (2003). The state of sustainable coffee: a study of the northern twelve major markets. London, England: International Coffee Organization.

Helleiner, E. (1994). States and the reemergence of global finance: from Bretton Woods to the 1990s. New York, United States: Cornell University Press.

International Coffee Organization (2018). NY coffee prices Database. Retrieved from http://www.ico.org/

International Coffee Organization. ICO annual reviews 2011/2012, 2012/2013, 2013/2014, 2014/2015, 2016/2017 retrospective. Retrieved from http://www.ico.org/documents/cy2012-13/annual-review-2011-12e.pdf

Lewin, B.; Giovannuci, D.; & Varangis, P. (2004). Coffee markets: new paradigms in global supply and demand. (The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Agriculture and Rural Development, Discussion Paper 3), Washington: World Bank. Retrieved from https://www.scirp.org/(S(lz5mqp453edsnp55rrgjct55))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=2039966

Paré, G.; Trudel, M.C.; Jaana, M.; & Kitsiou, S. (2015). Synthesizing information systems knowledge: a typology of literature reviews. Information & Management. 52 (2): 183–199. Retrieved from https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/4126344/mod_resource/content/2/2.4.Pare%20et%20al.%202015%20-%20literature%20review.pdf

Prebisch, R. (1950). The Economic Development of Latin America and its Principal Problems. New York: Economic Commission for Latin America. Retrieved from https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/29973/002_en.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Raynolds, L. T. (2000). Re-embedding global agriculture: the international organic and fair trade movements. Agriculture and Human Values, 17(3), 297-309, Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1007608805843

Redfern, A. & Snedker, P. (2002). Creating market opportunities for small enterprises: experiences of the fair trade movement. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Organization. Retrieved from http://www.oit.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/ ifp_seed/documents/publication/wcms_117707.pdf

Reinecke, J. (2010). Beyond a subjective theory of value and towards a ‘fair price’: an organizational perspective on Fairtrade minimum price setting. Organization, 17(5), 563–581. Retrieved from http://www.socioeco.org/bdf_fiche-document-3384_en.html

Reinecke, J.; Manning, S.; & von Hagen, O. (2012), The emergence of a standards market: multiplicity of sustainability standards in the global coffee industry, organization studies, 33(5), 6, 789-812. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=1970343

Renard, M. (January 2003). Fair trade: quality, market and conventions. Journal of Rural Studies 19(1):87-96.

Ruggie, J. (1982). International regimes, transactions, and change: embedded liberalism in the postwar economic order, international organization. Volume 36, Issue 2, International Regimes, p. 379-415. Retrieved from http://ftp.columbia.edu/itc/sipa/U6800/readings-sm/rug_ocr.pdf

Singer, H. (1950). The distribution of gains between investing and borrowing Countries, American Economic Review 40: 473-85.

Singer, H. (1984). “The terms of trade controversy and the evolution of soft financing: early years and the UN”, pp. 275-303 in Gerald Meier and Dudley Seers (eds), Pioneers in Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Singer, H. (1989). Terms of trade and economic development, pp. 323-8 in John Eatwell et al. The New Palgrave: Economic Development. New York: W. W. Norton.

United Nations (1949). Relative prices of exports and imports of underdeveloped countries. New York: United Nations. Retrieved from www.questia.com

VanderHoff Boersma, F. (2001). “Economía y Reino de Dios: neoliberalismo y dignidad opuestos que viven juntos”. Christus 723.

(Fecha de recepción: 11 de febrero del 2019 - Aceptado: 15 de mayo de 2019 - Publicado: 1° de octubre de 2019)