REVISTA

PRAXIS

83

e-ISSN: 2215-3659

Enero-junio 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/praxis.83.1

http://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/praxis

DECISION-MAKING MANAGEMENT IN PATIENTS WITH ADVANCED DEMENTIA AND DYSPHAGIA IN COSTA RICA: A CLINICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL ANALYSIS

LA TOMA DE DECISIONES EN PACIENTES CON DEMENCIA AVANZADA Y DISFAGIA EN COSTA RICA: UN ANÁLISIS CLÍNICO Y FILOSÓFICO

José Ernesto Picado Ovares

Geriatra Paliativista

Hospital Nacional de Geriatría, Costa Rica

Costa Rica

Allan González Estrada

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

Costa Rica

allan.Gonzalez.Estrada@una.ac.cr

Recibido: 21 de enero, 2021 / Aprobado: 30 de enero, 2021 / Publicado: 17 de febrero, 2021

Abstract

The use of feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia suggests several ethical concerns not only for healthcare professionals but also for the patient’s family. One point explored in this research deals with the symbolism associated with food and the idea of a good life and vitality (as seen in Costa Rica and in other Latin American countries). Subsequently, the request from families to use a feeding tube in a person with advanced dementia may be explained in terms of this association. Another point discussed in this research is the decision-making process between the family, the healthcare workers, and the patients themselves. Such discussions are examined in terms of the principle of autonomy and the principle of humanity to understand the desires and beliefs in the end-of-life decision. In the same manner, this research aims to investigate the reasoning process involved in the decision itself in terms of the modus ponens as a strong logical reasoning that leads to the decision. Yet, such a decision may be compromised when the modus ponens diverts into a fallacy by denying the consequences. Subsequently, this can derive into a chain of deductions that may undermine the consideration of the autonomy principle and the principle of humanity in deciding whether to use the feeding tube. This research also suggests the need for an extensive educative process to encourage the early decision of terminating a person’s life. Finally, this research makes an appeal for the evaluation of the laws governing end-of-life decision-making in Costa Rica, including medical and judicial policies.

Keywords: end-of-life care, ethic, feeding tube, decision-making, modus ponens, autonomy, principle of humanity, logic reasoning, bioethics, moral.

Resumen

El uso de tubos de alimentación en pacientes con demencia avanzada sugiere varias preocupaciones éticas, no solo para los profesionales de la salud, sino también para las familias del paciente. Un punto poco explorado, del que trata este escrito, es el del simbolismo asociado entre la comida y la idea de una buena vida y vitalidad (visto en Costa Rica y otros países latinoamericanos), ya que la solicitud de las familias, de utilizar sonda de alimentación en una persona con demencia avanzada, puede explicarse en términos de los razonamientos sobre esta asociación. De esta manera, el proceso de toma de decisiones entre la familia, el personal sanitario y los propios pacientes se vuelve complicado, no solamente desde el punto de vista ético, sino lógico y de simbolismos asociados. Tal discusión se analiza en términos del principio de autonomía y el principio de humanidad para comprender los deseos y creencias que participan en las decisiones sobre el final de la vida. En consecuencia, esta investigación tiene como objetivo indagar ese proceso de razonamiento involucrado en la propia decisión en términos del modus ponens, como un fuerte razonamiento lógico que conduce a la decisión. Sin embargo, tal decisión puede verse comprometida cuando el modus ponens se desvía hacia una falacia, al negar las consecuencias. Posteriormente, esto puede derivar en una cadena de deducciones que pueden socavar la consideración del principio de autonomía y el principio de humanidad para decidir si utilizar la sonda de alimentación. Esta investigación también sugiere la necesidad de un proceso educativo extenso para alentar la decisión temprana de terminar con la vida de una persona. Finalmente, esta investigación apela a una evaluación de las leyes que rigen la decisión sobre el final de la vida en Costa Rica, incluidas las políticas médicas y judiciales. Se presenta al final un cuadro con las consideraciones clínicas y éticas asociadas al uso de tubos de alimentación en pacientes con demencia avanzada.

Palabras clave: cuidados al final de la vida, ética, sonda de alimentación, toma de decisiones, modus ponens, autonomía, principio de humanidad, razonamiento lógico, bioética, moral.

Patients’ families and healthcare workers making end-of-life decisions regarding the use of artificial nutrition are one of the current debates in the philosophical and medical field that require an ethical framework. Although there are some guidelines for enteral feeding in advanced dementia patients (Stroud, M., Duncan, H., Nightingale, J., &, 2003), an ethical reflection is required for individuals lacking the mental capacity1 to participate in the decisions about their own healthcare.

This ethical framework is needed more than ever because, along with the growth of the world’s elderly population,2 and thanks to the advances in medical treatment, people with neurological disorders (such as advanced dementia) live longer. However, acquired brain injuries and intellectual disabilities make them a vulnerable population, and consequently they should be objects of moral protection. Although patients often present dysphagia and require artificial nutrition3 (devices such as nasogastric tubes or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [PEG]), little is known about the end-of-life decision-making debate and the deliberation itself (Anantapong, 2020), which is quite often ethically complex. Aside from this, in countries such as Costa Rica, research on the symbolic association with food and life in elderly people is limited.

On the side of healthcare workers, the principle of justice and not maleficence should be also considered, and addressing the patient’s autonomy and best interest should be underlined as an aspect that requires a delicate approach. It is not easy for the healthcare workers to make a decision on their own when a consensus with the family is not reached, which adds an initial stress to the decision-making process. The idea of artificially feeding an individual may be related to the belief that a person can recover, implying some degree of hope for the family. Nonetheless, the exact meaning of the use of an enteral feeding tube to maintain a human being alive could fail to be entirely understood by other members of the family, and a conflict during the decision-making process may arise.

Indeed, nutrition is a highly emotional topic from both sides, physicians and individuals, and the belief that people could improve their condition by eating, is understandable. In the case of elderly people with dementia, this requires not only a decision but also the awareness of how long the artificial nutrition will last. It should also be noted that if a person is not able to make a decision about their own healthcare, someone else must, and this may stress the fact that artificial nutrition may be against the individual’s wishes and desires. The World Medical Association’s Declaration of Malta states that forced feeding is never ethically acceptable (Association, 1991), implying that such a situation may derive ethical concerns for autonomy.

This research aims to explore the ethical aspects mentioned above, along with the framework for the decision-making process, emphasizing the idea that a decision should have its baseline in the theory of justice (veil of ignorance, Rawls), in the Kantian term of the doctrine of virtue (the respect for the individual is in first place), and in the notion of a practical love with others (benevolence in Kantian terms). Let us explore a case to further discuss the ethical concerns and understand the decision-making process.

A ninety-year-old patient with advanced Alzheimer’s, dementia, and severe immobilization. He presents protein-calorie malnutrition and multiple pressure ulcers, the main ones being grade three in the right trochanter, grade four in the sacrum and right trochanter. He suffers from severe pain as he heals his pressure ulcers. He lives with his wife and has three children. Two of them livein the United States and visit their father during the holidays. The children are shocked by the evident physical and mental deterioration of their father, in their words, “this is not my dad, if you had known how he was before”.

For three consecutive days, he presents hypoactive delirium, drowsiness, fever, and hyporexia. He enters the emergency room with a temperature of 38.5 °C, 110/60 blood pressure, 110 x heart rate. The patient is stuporous, his right basal crepitus is heard. Laboratory tests reveal leukocytosis of 17,300 with 90% segmented. Aspiration bronchopneumonia is also found, which results in him being admitted into the hospital. The doctors suggest the placement of a nasogastric tube (NGS) as he is not able to swallow, and his family fears he may die from hunger. The case is discussed with the family and it is documented that in the past, the patient had expressed to his wife that he did not want to have “hoses or tubes” introduced to keep him alive. In his words, “if I have to die, then let me die calmly, without tubes or anything.” However, the children insist on the need to place NGS so as not to “starve their father”, and give him the minimum quality of life. They consider that not placing the tube would mean a “passive euthanasia.” They even threaten to sue the medical center for malpractice if they do not agree to their request and the patient dies.

The wife enters into a crisis, making it difficult for her to make a decision. Doctors urge for a quick decision, generating a conflict between the family and the healthcare personnel. The emergency department’s lead physician decides that given the family’s inability to reach an agreement, he is going to make the final decision and that the family must respect the decision as he is the one in charge of the department, and his medical faculties entitle him to know what is best for the patient.

1. The view on food implications for the use of feeding tubes

The previous case is a good example of how ethical conflicts arising during the decision-making process could lead to a dead-end situation resulting in the decision being made by a healthcare professional, often falling into a fallacy of authority (also known as medical paternalism). Considering this, the following question may arise: why is the belief of artificial nutrition as a viable way to treat patients with dementia so accepted and widely spread? Scientific research has concluded that a patient with advanced dementia does not show benefits from improving their nutritional status4, as Nicola Simmonds (Simmonds, 2010), suggests in the article “Ethical issues in nutrition support: a view from the coalface”. Moreover, there is another equally important question: why do families insist on artificial nutrition as a feasible treatment for these patients? The answer to this question is obviously not easy, however, we can assume that it is due to the widely accepted idea that feeding a person will prevent them from dying. We can also assume a certain degree of religious belief from the family.

In Latin America, food is a marked symbol for family and values, food is associated with identity and family bonds. This suggests the idea of food as not just something that keeps people alive but also represents society and its members (Ruben Saldaña y Jr. George Felix, 2011). It is known that a person is a compilation of memories collected through family, friends, places and others, and food has a very particular place in patients with dementia. It is certainly a miserable and emotionally shocking experience to see patients not being able to feed themselves. Nonetheless, the aforementioned facts5 may be enough to direct the family’s wishes to a more palliative care6.

2. Autonomy and decision making on the use of feeding tubes

The idea of autonomy is key and sometimes neither the healthcare workers nor the patients and their families understand its meaning. The core idea of autonomy can be understood in terms of sovereignty7 over oneself (Mill, 1859), however, Kant understands autonomy in a more personal sense. In his view, the autonomy of rational agents is granted by the moral principles originated in the exercise of reason which authoritatively limit the way we act. In other words, there are laws that we set for ourselves, and thus, such rational agents are bound only to self-given laws (Kant, 2017). Nonetheless, autonomy can be assumed in terms of agency. Consequently, the idea of autonomy can be understood in terms of the capacity to critically assess our base desires and values, and to act on those that we endorse on reflection. Patients can decide by themselves in terms of their own desires, beliefs and so on, but the conflict becomes relevant when the person is no longer able to manifest such desires. To put it in different terms, the conflict with autonomy may be derived from an interpretation on an idea suggested by John Stuart Mill. In his view, autonomy is “one of the elements of well-being” (Mill 1859, ch. III). Indeed, viewing autonomy as an intrinsic value or as a constitutive element in the personal well-being may open the door to a generally consequentialist moral framework, while paying attention to the importance of self-government to a fulfilling life. In other words, according to consequentialism, the moral value of an action is its consequence. If this consequence produces the maximum happiness for the majority, the moral action is considered to be right.

Let us suppose a deliberation process where the family must determine if a patient needs to be connected to an artificial feeding tube or not. The decision may be determined to produce the maximum level of happiness for the members, leaving the patient’s wishes in last place. If the autonomy is placed in terms of a utilitarian framework (where the decision of happiness or well-being of the group (family) is placed above the wishes of an individual), then this may involve a problem for utilitarism itself. How could this be the case? A path to explore is the so-called principle of charity which states that charity governs the interpretations of the beliefs and utterances of others. Quine (Quine, 1960) and Davidson (1974) develop this idea further. According to Verheggen, Davidson’s principle of rational accommodation should include the desired attitudes as well as the beliefs of the proponent to “maximize” sense and “optimize” agreement for the coherence. In Davidson’s words, “the speaker to be responding to the same features of the world that [we] would be responding to under similar circumstances” (Verheggen, 2017, p. 98). He suggests that, what influences the decision of the family, is not the idea of autonomy but the interpretation of the patient’s wishes, not just something expressed previously, but rather something that may produce the maximum benefit or happiness for the family. Under this circumstance, where the interpretation is to seek coherence from the utterance of the individual, the decision will pass through this charity principle. Healthcare workers should apply this principle as well. However, this choice is ultimately the physician’s decision in the medical paternalistic practice.

A way to conserve the individual’s autonomy is to apply the principle of humanity. Broadly speaking, according to Dennett, this principle states that when interpreting a speaker, we must assume that the beliefs and desires of both parties (listener and speaker) are connected via “the propositional attitudes one supposes one would have oneself in those circumstances.” (Dennet, 1987, p. 343). In other words, could be suggested that we could exercise a moral sentiment via our linguistic intentionality, that is to say, the idea of empathy suggested by Smith (1759) and Hume (1780), taken further by Kant with the principle of harmony (1797), is likely to be applied. According to Kant:

[A]ll moral relations of rational beings, which involve a principle of the harmony of the will of one with that of another, can be reduced to love and respect; and, insofar as this principle is practical, in the case of love the basis for determining one’s will can be reduced to another’s end, and in the case of respect, to another’s right. (Kant, 1797/2017, p. 248)

The philosopher suggests that not only do we have rights but also duties to others, and one of these duties is imperative to the others. The reason why it is our duty is because it also means the happiness of others. Thus, a principle of humanity may guide the decision and, consequently, the person’s autonomy and previous wishes8. This may solve the apparent problem of the deliberation of autonomy. However, the decision could be harder than expected. Not only is it the deliberation process on whether or not to put a feeding tube into a patient, but also on eventually removing the tube, which may terminate the life of the person, and this is part of a chains of reasonings.

3. The logic of decision-making where the ethical decision starts

One of the reasons why this discussion is relevant is the fact that when we talk about a decision, somehow, we are at the same time talking about our logical way of thinking, and this may have many consequences. This is true because we tend to assume the principle of causality (Hume, 1764). To illustrate this point, the logic of [(p ⟶ q) ∧ p] ⟶ q may be explained as follows: if “p” implies “q”, and “p” is true, then “q” must also be true. An example of this could be the following reasoning:

If I do a lot of sports, then I am tired.

I do a lot of sports.

_______________________________

Therefore, I am tired.

Intuitively, this reasoning seems to be correct, however, according to Ram and Eiselt the reasoning process is more complex, there is a central role of modus ponens in the human cognition (Ashwin Ram y Kurt Eiselt Eds., 1994), moreover, Pfeifer in the book Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Imprecise Probability: Theories and Applications sugested that our logic prediction could be complicated if the logic arguments are derived from negations in the reasoning process (Pfeifer, 2007, p. 347, 348). Hence, according to such findings, people employ inference rules that guarantee high probability conclusions if the premises are highly probable. Accordingly, in an end-of-life decision, the modus ponens reasoning could have a great impact on the decision. Let us consider the following reasoning:

If the doctor puts in a feeding tube, then X will not die.

The doctor puts in a feeding tube.

_______________________________

Therefore, X will not die.

Here the reasoning seems to be coherent with the probabilities known by an epistemological process of testimony recollected by the family to make a decision. This is possible because our minds are equipped with an inferential rule corresponding to the modus ponens. However, there could be a problem with such reasoning, a problem that could lead us to a fallacy, and it is affirming the consequence that may take the form of the following reasoning:

If the doctor puts in a feeding tube, X will not die.

X dies.

________________________________________

Therefore, the doctor did not put in a feeding tube.

The problem lies in the fact that our minds are not equipped with a rule to such inference, and so, the reasoner must engage in a chain of deductions to arrive at the conclusion. According to Legrenzi, “formal rule theories predict that the difficulty of a deduction depends on two factors: the length of the formal derivation, and the unavailability (or difficulty of use) of the relevant rules” (Legrenzi, 1993, p. 41). In other words, the patient would die for a lot of reasons, not necessarily because of a feeding tube issue. However, in the mindset of the person, such reasoning could be “valid” given this logical fallacy. In consequence, since our minds are not equipped to solve this dilemma, a chain of deductions may start, and this chain of deductions may not only start in the present but also in the future. The deliberation process between family, healthcare workers and social workers may start with a reasoning about future events, a reasoning that may not follow a valid logical form. People can engage with many reasonings that may require many deductions that depart from a wrong logical construction. From here, decision makers and healthcare workers need to take this into account to simplify the decision-making. Appealing to Occam’s razor, when presented with two explanations, the simple one is the correct; ethical decisions cannot be divorced from the epistemological and logical reasoning of the world. Consequently, appealing to the principle of humanity, propositionally thinking about the patients’ desires and beliefs, and understanding their utterances in a logical, correct way may avoid unnecessary discussions.

4. The feeding tube: treatment or relentless therapy

In his book “Philosophy of Medicine”, Alex Broadbent notes a very useful division: cure, therapy, and medicine. For the author, medicine is the profession where cure and therapy play an important role (Broadbent, 2019, p. 36). In his words, “…. Therapy [may] be understood as any intervention that alleviates the suffering or harm caused by disease but does not necessarily remove it.” (Broadbent, 2019, p.36). Accordingly, treatment may be understood as encompassing both, therapy and cure. Hence, the idea of the feeding tube as a treatment does not describe the whole picture and problem of the feeding tube, rather, it could be preferably called a sort of therapy with the goal to alleviate a given suffering.

In the case of elderly people with dementia, the discussion of the feeding tube is quite complicated, as it is related to the idea of what food represents for Latin American people (particularly in Costa Rica). Equally important, semantically speaking, a person can understand therapy and treatment as synonymous, causing some degree of linguistic confusion that may derive in the suffering of a person who may require the use of a feeding tube. Nonetheless, this topic is not an easy one to discuss. On the one hand, there is the physician’s obligation to try to save lives, on the other hand, the decision usually made is full of ethical considerations9 .

It is clear that the idea of placing a feeding tube in patients may be understood as a therapy, rather than the idea that the right of feeding the patient is something families need to observe at all times. Why is this possible? As noted earlier, in the mindset of a community, food is understood as a synonym for health. A slim person is normally associated, in colloquial terms, with a sick individual. On the contrary, a person of medium build is seen as healthy (Zaccagni, Luciana, Rinaldo, Natascia, Bramanti, Barbara, Mongillo, Jessica y Gualdi, Emanuela, 2020). Thus, as soon as patients present eating difficulties, and the alternative of a feeding tube is suggested, the family would put the right to be fed first. This procedure may cause a great deal of suffering for the patient. Especially when the decision involves not using or removing the feeding tube. Physicians may not take the whole responsibility for this last step of suffering in a patient. There are many other social and mindset issues that are equally or more important. For this reason, palliative care teams should be contacted even before a patient who requires a feeding tube enters the last stages of dementia.

It is imperative that social campaigns of sensibilizations start in society. If done so, citizens may assume the responsibility for their end-of-life provisions, and declare (based on the information available), their desires for end-of-life care. Additionally, the laws regarding this topic need to be more flexible to allow the least amount of suffering possible in people who may require such end-of-life therapies. The goal of avoiding any form of relentless therapy that may not alleviate any suffering, as well as the age of the patient, must both be taken into consideration.

In Costa Rica, where the elderly population is growing, a whole discussion as a society has become necessary. In agreement with Buckley (Buckley, T., Crippen, D., DeWitt, A.L. et al, 2004), when declaring that, “common law courts are poor substitutes for family in end-of-life decision-making because they do not apply the standards of the family, and instead apply legal standards that are easily manipulated”, laws responding to an ethical reflection do not necessarily adopt beneficence for all, and the lawmakers’ response to a particular moral view may add a great deal of pressure on physicians who ultimately will try to make a decision where consensus is not reached. However, to return to a point discussed previously, a deliberated process based on the principles of autonomy and humanity needs to be conducted to ensure the maximum beneficence for all people involved in the end-of-life decision for a person.

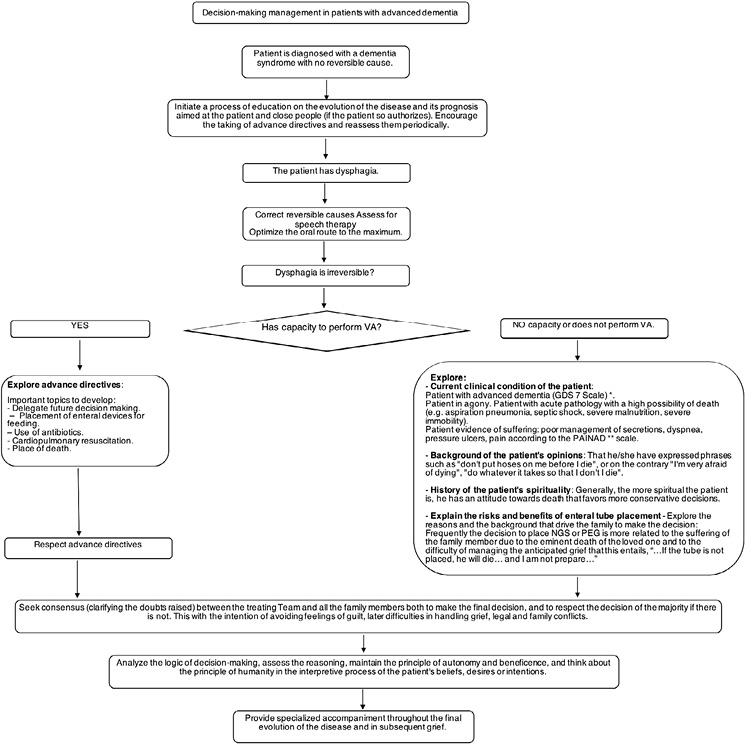

In summation, we examined some ethical issues with the use of feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia while considering the mindset of cultures in countries such as Costa Rica within the context of how the social value given to alimentation is understood in Latin America. One of the main ethical concerns is the decision-making process, not only for the person receiving the feeding tube but also for the family and the physician in the case where there is not an a priori instruction from the patients themselves about end-of-life. We explored the idea that the principle of humanity and autonomy needs to be understood to help with the decision, and this decision needs to be explored through the reasoning process that people go through. This ethical decision requires an epistemological and logical reasoning of the world. The idea of the semantic understanding of desires and beliefs must be aligned with the principle of beneficence, ensuring minimal suffering for the patient. This could be resolved by developing an educative process that includes all people involved in the decision-making process. Only in this way, will the possibility of an early decision greatly improve the quality of life for patients with dementia, and their suffering. The following flowchart is an attempt to summarize the main points in the decision-making process:

Figure 1: Flow chart for decision making in the process of considering enteral tube placement in patients with advance dementia. Source: from the authors.

* GDS (Global deterioration scale).

**PAINAD (Pain assessment in advanced dementia scale).

Anantapong, K., Davies, N., Chan, J., McInnerney, D., & Sampson, E. L. (2020). Mapping and understanding the decision-making process for providing nutrition and hydration to people living with dementia: a systematic review. BMC geriatrics, 20(1), 520. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01931-y

Ashwin Ram y Kurt Eiselt Eds. (1994). Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Atlanta: Routledge.

Association, W. M. (1991, Noviembre 12). Wma declaration of malta on hunger strikers. Retrieved from https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-malta-on-hunger-strikers/

Broadbent, A. (2019). Philosophy of medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buckley, T., Crippen, D., DeWitt, A.L. et al. (2004). Ethics roundtable debate: Withdrawal of tube feeding in a patient with persistent vegetative state where the patients wishes are unclear and there is family dissension. Critical Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2451.

Dharmarajan TS, Unnikrishnan D, Pitchumoni CS. (2001). Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and outcome in dementia. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2556-2563 .

Dennet, D.C. (1987). The intentional stance. The MIT press.

Kant, I. (2017). The Metaphysics of Morals. Cambridge: Cambridge Universtiy Press.

Legrenzi, P. (1993). Focussing in reasoning and decision making. Cognition, 37-66.

Mill, J. S. (1859). On Liberty. London: John W. Parker and Son, West Strand.

Nations, U. (2019). World Population Ageing 2019. New York: United Nations.

Pfeifer, N. (2007). Human reasoning with imprecise probabilities: Modus ponens and Denying the antecedent. In V. J. DeCooman G., Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Imprecise Probability: Theories and Applications (pp. 347-356). Praga: Publons.

Quine, W. &. (1960). Word and object: An inquiry into the linguistic mechanisms of objective reference. London: John Wiley.

Rome, R. B., Luminais, H. H., Bourgeois, D. A., & Blais, C. M. (2011). The role of palliative care at the end of life. The Ochsner journal, 348–352.

Ruben Saldaña y Jr. George Felix. (2011, Enero 1). Orale! Food and Identity Amongst Latinos!. Retrieved from Curate ND: https://curate.nd.edu/show/nz805x24b3k

Simmonds, N. J. (2010). Ethical issues in nutrition support: a view from the coalface. Frontline gastroenterology, 7-12.

Stroud, M., Duncan, H., Nightingale, J., &. (2003). Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. British Society of Gastroenterology, vii1-vii12.

Teno, J. M., Gozalo, P. L., Mitchell, S. L., Kuo, S., Rhodes, R. L., Bynum, J. P., & Mor, V. (2001). Does Feeding Tube Insertion and its Timing Improve Survival? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 1918–1921.

Verheggen, C. (2017). Rule-following and charity, Wittgenstein and Davidson on meaning determination. In C. V. Ed., Wittgenstein and Davidson on Language, Thought, and Action (pp. 69-96). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zaccagni, Luciana, Rinaldo, Natascia , Bramanti, Barbara, Mongillo, Jessica y Gualdi, Emanuela. (2020). Body image perception and body composition: assessment of perception inconsistency by a new index. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2-8.

1 This means diminished autonomy.

2 The population group of the elderly will be the group with the highest growth in the world. By 2050, the proportion of people over 60 will double, reaching 22% of the world’s population (WHO, 2018). These changes in the population pyramid will impact both the prevalence and the incidence of non-oncological diseases associated with age where dementia syndromes can be included. According to Alzheimer’s Disease International for that year, 131.5 million older adults will have a diagnosis of dementia, with this disease increasing most rapidly in developing countries (Nations, 2019).

3 According to José Ernesto Picado Ovares, co-author of this article, in the Hospital Nacional de Geriatría Doctor Raúl Blanco Cervantes de Costa Rica, from 210 patients with advance dementia 159 did not use feeding tube, and 51 did, globally 95% of the patients with advance dementia will have issues to swallow.

4 MacFie J. Ethics and nutrition. In: Gibney MJ, Elia M, Ljunqvist O, et al., eds. Clinical nutrition. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2005:132–45. Andrews MR, Geppert CMA. Ethics. In: Gottschlich MM, DeLegge MH, Mattox T, et al., eds. The A.S.P.E.N. Nutrition Support Core Curriculum: a case-based approach—the adult patient. Silver Spring: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 2007:740–60.

5 The scientific literature is clear in recommending against these actions. Their placement in this population is risky. It is associated with an increase in mortality, morbidity and hospitalizations (Dharmarajan TS, Unnikrishnan D, Pitchumoni CS, 2001). Mortality can be up to 28%, according to different publications 24. 64% of patients will have a 56-day survival after the procedure and around 20% will require an early repositioning of the device (Teno, J. M., Gozalo, P. L., Mitchell, S. L., Kuo, S., Rhodes, R. L., Bynum, J. P., & Mor, V. , 2001).

6 Palliative care is responsible for alleviating the suffering of individuals and families facing a terminal illness. Dementia is a terminal disease that shares similarities with other terminal diseases but has its own characteristics that make an approach different and highly complex (Rome, R. B., Luminais, H. H., Bourgeois, D. A., & Blais, C. M., 2011, p. 248).

7 Indeed, according to Mill, “…In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign” (Mill 1859, ch. III).

8 Thus the anticipated will is something that it is required to be discussed with the society as a whole, from all hospitals and healthcare workers related with the elderly a sensibilization campaign in order to discuss the autonomy and wishes of the elderly for their future treatment is required.

9 Indeed, medicine is full of ethical issues, one is if the goal of medicine is pain relief or the cure as a whole, some authors like Broadbent suggests that pain relief is a use of medicine and medical knowledge but not a goal per se of medicine (Broadbent, 2019, 0. 46), sedation is an example of this, cure always wins.

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.

Escuela de Filosofía, Universidad Nacional, Campus Omar Dengo

Apartado postal: 86-3000. Heredia, Costa Rica

Teléfono: (506) 2562-6520

Correo electrónico revista@una.ac.cr

Sitio web: https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/praxis