|

REVISTA 95.1 Revista Relaciones Internacionales Enero-Junio de 2022 ISSN: 1018-0583 / e-ISSN: 2215-4582 doi: https://doi.org/10.15359/ri.95-1.4 |

|

|

|

Defense policy shaping foreign policy. An alternative interpretation through the study of the Argentine-Chilean RELATIONS1 política de defensa moldeando la política exterior. Una interpretación alternativa MEDIANTE LAS RELACIONES Ezequiel Magnani2 ORCID: 0000-0002-6099-9325 Maximiliano Luis Barreto3 ORCID: 0000-0002-2932-0046 |

||

Abstract:

Which is the relationship between defense policy and foreign policy? How does defense policy influence foreign policy? The investigation is based on both questions. After a review of Argentinian literature analyzing the link between these policies, the article presents a new way of approaching the relationship between national defense and foreign policy based on the geopolitical concept of “axial point”. In this sense, the research suggests that, unlike traditional interpretations that place national defense as a secondary and complementary sphere to foreign policy, it is possible to argue that the former has a strong impact and influence on the latter. To empirically illustrate this new way of seeing the relationship between both policies, the article analyzes –using qualitative methodology linked to a single case study and based on the analysis of official documents and literature from that period– the bilateral relationship between Argentina and Chile, taking as central point of the analysis the Beagle Channel Conflict and considering the channel as an axial point. The paper concludes by showing how the case study illustrates the way in which defense policy impacts and influences foreign policy.

Keywords: Argentina; Axial points; Chile; Defense policy; Foreign policy; Geopolitics

Resumen:

¿Cuál es la relación entre la política de defensa y la política exterior? ¿De qué forma la política de defensa influye en la política exterior? El trabajo se desarrolla en función de ambos interrogantes. Luego de presentar una revisión de la literatura que analiza la vinculación entre dichas políticas, el trabajo presenta una nueva forma de aproximarse conceptualmente al tipo de relación que tiene la defensa nacional con la política exterior a partir del concepto geopolítico de “punto axial”. En tal sentido, la investigación sugiere que, a diferencia de las interpretaciones tradicionales que colocan a la defensa nacional como un ámbito secundario y complementario a la política exterior, es posible argumentar que la primera tiene un fuerte impacto en la segunda. Para ilustrar empíricamente esta nueva forma de ver la relación entre ambas políticas, el artículo analiza –utilizando una metodología cualitativa vinculada al estudio de caso único y basada en análisis de documentos oficiales y literatura de dicho período– la relación bilateral entre Argentina y Chile tomando como punto central de análisis al Conflicto del Canal Beagle visto como un punto axial. El trabajo finaliza argumentando que el caso de estudio evidencia la forma en la que la política de defensa impacta en la política exterior.

Palabras clave: Argentina; Chile; Geopolítica, política de defensa; política exterior; puntos axiales

The relationship between defense policy and foreign policy has traditionally been analyzed in Argentinean literature considering that the former is subordinate to the latter. This analytical orientation has led to the fact that, in these studies, national defense policy is studied not based on its own characteristics but on how its design can contribute to achieving the State’s foreign policy objectives. In other words, these works do not consider the strategic particularities of defense policy, linked to the recognition of strategic assets to defend, the possible ways to defend them, the identification of threats, and the analysis of regional and international scenarios. By not considering these elements of national defense, a key aspect of the political link between defense and foreign policy remains virtually unexplored: the way in which foreign policy is impacted by defense policy.

Thus, this article reviews the existing studies on the defense-foreign policy relationship in Argentina and problematizes the current analytical approaches. By entering in this theoretical discussion, it seeks to complement the present literature by revaluing the particularities of national defense, especially around the strategic assets that a State seeks to protect through the design of defense policy, whose articulation becomes apprehensible through the conceptual proposal of the so-called “axial points” (Barreto, 2020). Consequently, the cornerstone of the work lies in the normative assumption that the consideration of the strategic aspects of national defense is a necessary condition to reflect –from an unconventional point of view– the relationship between defense and foreign policy. Therefore, exploring alternative visions regarding how defense policy and foreign policy are combined also implies highlighting a dimension of the literature on national defense that has not been studied yet. Specifically, this issue is linked to the strategic aspect of defense policy (Magnani and Barreto, 2020; Magnani, 2021) and inquiries about the strategic features of national defense policy, including the definition of the strategic assets, the design of the military instrument, the identification of external threats, and the analysis of the regional and international context.

Likewise, this approach to national defense implies contributing, in a secondary way, to the hierarchization of the discussion regarding the foundations of national defense (Battaglino, 2015). That is, it seeks to contribute to the discussion that deals with the question related to “the reasons why countries allocate more or less resources to their armed forces” (Battaglino, 2015: 207). In this way, highlighting the relevance of defense policy in its relationship with foreign policy implies investigating the importance of national defense for the State based on its defense objectives, its international insertion strategy, and its link with other areas of government like the field of foreign policy.

The cornerstone of the article is the argument that defense policy can impact foreign policy insofar contributes to changing perceptions regarding which actors are threatening and, consequently, by influencing the definitions of the external concerns that the State must consider when designing its foreign policy. To empirically illustrate this reasoning, the bilateral relations between Argentina and Chile are analyzed during the territorial dispute for the sovereignty of the Picton, Nueva and Lennox islands of the Beagle Channel, with special emphasis on the 1970s decade. In methodological terms, a single case study is carried out and qualitative techniques linked to synchronous historical-descriptive analysis are used –based on Argentine documentary material– to analyze the link between defense policy and foreign policy presented in the theoretical section. The case study falls within what Lijphart includes in his typology as a deviant case study, where “the case is designed based on its theoretical importance. It is selected because it deviates from the trend foreseen in a previous theory or generalization” (Lijphart, 1971: 691-693). Therefore, the objective of the article is to reevaluate the traditional conceptualization of foreign and defense policy by analyzing the Argentine-Chilean bilateral relations regarding the territorial dispute for the sovereignty of the islands of the Beagle Channel. In addition, this article considers the limitations of the single case study, where the external validity and the possibility of generalizing are put aside, giving priority to the new insights that can only be obtained by the study of a specific case. Hence, it follows from this reasoning that the results of this investigation are limited in scope to this case. However, the conclusion of the article contributes to the general debate in Argentine literature related to how the relationship between foreign and defense policy should be studied and it problematizes the currently dominant views.

The article continues as follows. In the next section, a review of the existing literature related to the study of the connection between defense policy and foreign policy is carried out. Subsequently, a new way of considering the relationship between defense policy and foreign policy is presented based on the introduction of the concept of “axial point”. Then, the case corresponding to the evolution of the bilateral relationship between Argentina and Chile is illustrated as a function of the resolution of the dispute over the islands of the Beagle Channel to account, in empirical terms, for the convenience of applying the new theoretical framework that suggests a new way of conceptualizing the relationship between defense policy and foreign policy. Finally, the last section develops the implications that the analysis of the case has for the debate regarding the link between national defense and foreign policy.

II. The place of defense and foreign policy in the literature

Studies on the relationship between foreign policy and national defense policy are scarce. In general terms, the studies that have investigated the link between defense policy and foreign policy have focused on evaluating the way in which defense policy contributes, in a secondary way, to achieving foreign policy objectives. This implicates moving aside from the analysis of the process in which foreign policy is transformed as a function of changes in defense policy, especially, considering the definition of external state actors that constitute a threat to the interests of the State.

The first generation of these proposals emerged during the 90s, a decade in which Argentina saw a transformation in its military instrument, both in terms of the consolidation of the “basic consensus”4 and the use of the Armed Forces by the political leadership. The need to find a role for the military instrument in a national scenario still plagued by the urgency of strengthening the democratic government system allowed for in-depth studies related to national defense. Thus, the new studies inquired about the role of national defense vis-à-vis foreign policy objectives and the way in which defense policy could contribute to achieving them (Tokatlián, and Pardo, 1990; Russell, 1992a, 1992b, 1992c, Paradiso, 1993; Tokatlián and Caravajal, 1995; Tokatlián and Russell, 1998).

At the beginning of the 21st century, it is possible to identify a second generation of studies that specifically focused on analyzing the relationship between defense policy and foreign policy. Although these studies cannot be considered as belonging to a uniform line of research, they all have in common the interest in establishing connections between both policies with aiming to evaluate the way in which they were articulated and individually affected by this link.

Eissa (2013) is considered a pioneer in this field. The author analyses the nature of the relationship between defense policy and foreign policy, establishing that the guidelines of the first are reflected in the second. This assertion is empirically illustrated from an analysis of Argentine foreign policy considering the main guidelines of the “basic consensus”.

The mention of this relationship is made in a later article by the same author, where he emphasizes that the link between the two policies constitutes a self-dimension –the international one– of defense policy (Eissa, 2017). Then, there is a second generation. In this generation, it is possible to identify those articles that inquire about how the design of defense policy contributes to achieving the objectives of the international insertion of a given country. These articles explore the way in which foreign and defense policy complement each other to achieve the international objectives of the State.

Meanwhile, Calderón (2018) addresses, from an intermestic perspective, the changes in defense policy that occurred in Argentina from the Macri administration a period where this policy went from a strong subregional commitment to relative globalism. Here, the defense policy was executed jointly with a foreign policy that aimed to bandwagon Western-developed countries, which implied a progressive distancing from its traditional South American partners.

In the same path, Busso and Barreto (2020) investigate the role of defense policy during the period 2003-2019 and the changes it had after the arrival of the Macri administration. During the analyzed period, the authors conclude that foreign policy had a strong influence on defense policy. Therefore, defense policy was rearranged to the objectives of international insertion and to the country’s development model. Thus, defense policy is approached from its international dimension, implying an analysis of those aspects of the defense policy that can contribute to the objectives of international insertion and development of the country. In this sense, the methodology of the article includes the analysis of documents signed by Argentina with other States in matters of security and defense and projects related to regional cooperation in that area.

In this framework, an incipient third generation of studies can be identified. This research reflects about the way in which a certain foreign policy orientation impacts key factors of the national defense of a State, contributing to the change in the strategic orientation of that policy. Battaglino (2019) advances in this line by empirically showing how the guidelines and foreign policy preferences of the Macri administration impacted the perception of threats from the Argentine State and the choice of the military instruments used by the State to repel these threats.

Based on the identification of Argentina’s approach to the United States in international issues and by using the Copenhagen School approach, Battaglino (2019) analyzes the way in which the use of discursive mechanisms by the Macri administration impacted the perception and construction of new threats. This author also reflects on how these mechanisms influenced the mobilization of resources and the state agencies in charge of dealing with them.

Frenkel (2020) is identified within this generation of works. Based on the use of the two possible logics –autonomy/acquiescence– of international insertion identified by Russell and Tokatlián (2013), he illustrates the impact that the acquiescent logic of international insertion during the Macri administration had in the participation of Argentina in the South American Defense Council of South American Union (Unasur for the Spanish acronym).

Magnani and Altieri (2020), for instance, also use these insertion logics to reflect on the change in Brazil’s defense policy after the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff. In this case, the authors argue that after the political trial, Brazil’s foreign policy was strongly marked by a rapprochement to the United States in matters of defense and international security affecting its defense policy regarding the identification of the regional scenario and the perception of threats.

Thus, this article aims to generate a new approach to the link between defense and foreign policy, emphasizing the way in which the former can also impact the latter. Likewise, the research complements these studies by shedding light on the way defense policy can modify key elements of the relationship between two or more States related to changes in the perception of the other (e.g., passing through a logic of enmity/rivalry to another of amity) (Wendt, 1999). In this way, giving preponderance to defense policy, particularly, focusing on the redefinition of external threats, implies attention on aspects scarcely covered in the literature but with specific impact on the foreign policy of the States. In methodological terms, defense policy is placed as an independent variable that impacts, facilitating or hindering, foreign policy and the type of relationship between two States. Therefore, foreign policy is established as a dependent variable.

In this research, the axial points are framed as part of the national defense literature that studies those strategic issues. If we consider the strategic dimension of defense policy as the aspect of defense policy “where the leaders of a State determine as their main objective the preservation of certain national assets and establish the most optimal way to do so in consideration of the external threats perceived and the identified regional and international scenario” (Magnani, 2021), it is possible to establish that the axial points introduced in this article are placed within the first point regarding the national assets that a State seeks to protect.

Therefore, the utilization of the axial points approach as a theoretical tool (Barreto, 2020) constitutes a contribution to the studies of national defense by allowing to inquire about the most elementary factor in defense policy: material and objective strategic assets that are within a sovereign territory and that the States seek to protect. In this context, the axial points entail a strategic aspect of national defense; and it is because of them that the relationship between defense policy and foreign policy can be analyzed in a different and non-subordinated way.

III. Defense policy and foreign policy: a non-hierarchical relationship

Although defense policy is analytically separable from foreign policy, it should not be forgotten that the priority of foreign policy in this analysis responds to theoretical and methodological preference or research convenience. Therefore, if one appears subordinate to the other is the consequence of a certain decision. Considering that, from a legal perspective, it can be argued that defense policy should be channeled within the limits and guidelines of foreign policy (for example, it is evident that an agent of the Defense Ministry cannot meet with an interlocutor not authorized by foreign policy).

Nevertheless, this does not mean that the relationship among them is completely rigid, and it follows an absolute degree of structure. It is also evident that the defense agency can persuade foreign policy officials about the relevance of the meeting with an interlocutor that was not authorized at the first time. In this case, it would be defense policy that would be shaping the preferences of foreign policy decision-makers, a situation that empirically escapes the researcher when using a defense policy subordination theoretical approach.

Considering that point, one might ask how useful it is to argue that defense policy is subordinated to foreign policy. This does not mean validating a normative aspiration that defense policy should shape foreign policy, but it is worth asking why the present literature does not contemplate this reverse situation. If a large amount of literature focuses on the study of domestic constraints of foreign policy (Van Klaveren, 1992; Soares de Lima, 1994; Lasagna, 1995; Rosenau, 2006; Busso et al, 2016), one might ask for a second question, in terms of causality or affectation, related to the difference between the influence of the domestic constraints on foreign policy and the influence of defense policy on foreign policy.

Furthermore, in a scenario in which it is increasingly common for a ministry or secretariat to have de jure or de facto an area reserved for world affairs (“mini-chancelleries”) or where it is observed how the Ministry of Economy compete with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Tokatlián and Merke, 2014: 264), why the literature does not inquire about the impacts of defense policy on foreign policy?

The hierarchy between both policies is not philosophically discernible for two reasons. First, considering the State as a monolithic actor, it is observed that both are –at the most general level– equal tools of foreign behavior. That means the moment in which the covenanters abdicate their will and capacity, strength, and instruments of self-protection and concentrate them monopolistically in the State (Saint Pierre, 2012: 42). Second, more specifically, they derive from the distinction –which is a consequence of the pact– between a domestic space (within the State) and an external one (where the State coexists with other units) and besides from the nature of the violence that corresponds to each. In this context, both are public policies that are preferably related to the external environment where there are other sovereign units coexisting with the State and where it is contractually lawful to use defensive and lethal violence5. Considering these arguments, a hierarchical relationship between both policies is not clearly discernible:

a)It could be argued that defense policy appears to have an instrumental role and, therefore, it should be subordinate to foreign policy. This is only justifiable with a reductionist vision of defense associated only with moments of high levels of pugnacity and violence.

It could be argued that foreign policy appears subordinate to defense policy since issues related to violence are agreed upon in the pact. This is only justifiable by holding that violence is the rule and that foreign policy corresponds to small moments of peace, restricting it most of the time.

In short, this fictional argument states that both are constituted –without a hierarchy between them– from the same foundations and sheds light on the nature of social construction that public policies have, changing throughout the history of the Nation-State. Then, it is convenient to think about feedback or interweaving between both policies and try to avoid sharp analytical separations. All this by acknowledging that there is a certain legal priority in each country. Both policies start from the same point that is the State, so both are subsidiaries of it, and they are deployed considering its objectives.

At this point, it is evident that those readings that consider such public policies as exogenously determined do not seem to be convenient. Although in the fiction of the pact, both policies appear related to the demarcation of the external environment, it was observed that their reason for being is found in the subjects who have made the pact. On a practical level, this means that defense and foreign policy agents have the same material to work on. For this reason, the external projection of these policies must not occur in a dissociated manner. On the contrary, it is necessary that foreign policy planning emerges from a process of feedback process among them. Both policies can be seen as tools that complement each other and work in a coordinated manner.

IV. The axial points in the defense policy-foreign policy relationship

Two issues summarize the affirmations above: a) there is no natural hierarchy between defense policy and foreign policy (except for the legal ordering of each State6) and b) it is evident that there is a founding connection between both and the domestic sphere. This leads to avoid studying the relationship between them by subordinating defense policy to foreign policy. Also, it allows to attend to the characteristics of the defense policy by its own features and not only based on how its design can contribute to achieving the State’s foreign policy objectives.

Considering these premises, it is possible to ask three questions: How is this relationship crystallized in order to be understood? How is the universe of elements regarding these policies organized? Which tool shows the crossroads between defense policy and foreign policy?

The article proposal is framed in the previous discussion regarding the foundations of national defense (Battaglino, 2015). The formulation considers the founding relationship that exists between the domestic level and defense policy and foreign policy, while considering that the total definition of both is obtained by including the external level in the analysis. The proposal is analyzed from an International Relations perspective in which the external scenario is always discernible (Castaño, 2003) not only as a contextual element (simple scenario in which the country is framed) but as a key element in the definition.

In a theoretical sequence, the starting point is the construction of a conceptual framework that allows a systematic inclusion of different elements of the domestic setting in which both policies are based in order to consider the external scenario afterward.

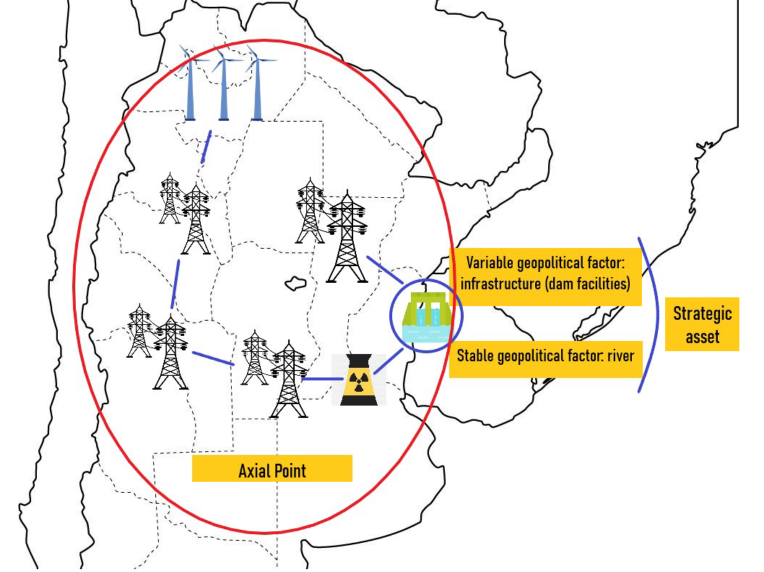

The starting point is given by the concept of geopolitical factor, the smallest particle in the outlined conceptual framework and linked to a set of circumstances or conditions. Often, these factors are classified as a) stable geopolitical factors: for example, a particular physical structure (suppose a mighty river); and b) variable geopolitical factors: infrastructure (dam facilities). When the factors are grouped together, they constitute a “strategic asset” (following the example, a hydroelectric complex: river plus the utilization facility). Here, the strategic nature is not intrinsic to the asset but belongs to a larger conglomerate (e.g., the Argentine Interconnection System, SADI) which entails an “axial point”7 of the Argentine defense system. That is a strategic axis or node for the defense of the country.

As the defense policy and foreign policy, the definition of the axial point relies on external variables: the SADI, as an axial point, acquires its strategic fullness when it is understood as a conglomerate to defend from “others” that are in the outer world, an external threat whose definition is intrinsic to the defense policy (Magnani, 2021). Indeed, the axial point provides support for the crossover between defense policy and foreign policy. Both policies based their existence and affirm their identity by being the channels in which the State is linked with the regional and international sphere. The axial point is defined as a concept impregnated by this dichotomy and whose characteristics are of interest to both public policies.

Image Nº 1. Representation of axial points

Source: Own elaboration

V. Redefinition of threats in defense policy and reconfiguration of foreign policy interests: Argentina in the dispute over the Beagle Channel

Relations between Argentina and Chile until the resolution of the dispute over the sovereignty of the Nueva, Lennox and Picton Islands of the Beagle Channel in 1984 (Image Nº 2) were historically characterized, mostly, by recurrent diplomatic tensions and military crises due to their differences regarding territorial delimitation and the mutual distrust. Just after the signing of the Tratado de Paz y Amistad (translated as Treaty of Peace and Friendship) in November 1984 (Cancillería Argentina, 1984) that both States started to move away from the relationship patterns characterized by enmity and towards bilateral relations characterized by the absence of threat perceptions and greater certainty regarding intentions and interests of each other.

Therefore, it is possible to argue that just until the signing of the Tratado de Paz y Amistad in 1984, which had a strong and positive impact on the improvement of the bilateral relations of both countries (Church, 2008), the relationship between Argentina and Chile was defined as having a high level of pugnacity because of the conflicts related to the definition of the territorial delimitation between them. The main territorial dispute was linked to the so-called “Beagle Conflict”, that is, the impossibility of reaching an agreement regarding the sovereignty of the Nueva, Picton and Lennox Islands.

Image Nº 2. Picton, Lennox and Nueva, Islands of the Beagle Channel with their sovereignty in dispute until 1984

Source: Own elaboration

Although the dispute over the sovereignty of the Beagle Channel Islands led to several tensions throughout bilateral history, the period of greatest conflict took place during the 1970s decade (Villar Gertner, 2014). The conflict starts after the fall of the colonial order due to the gaps left by Spanish legislation and the lack of Argentine and Chilean presence in the southern zone (Lacoste, 2005: 68). Despite both countries having signed in 1855 a treaty that recognized the validity of the principle of uti possidetis iuris of 1810 as a general criterion to establish the limits of both jurisdictions, it was not clear which were the milestones that, in the territory, supposed the international division. In fact, in those days, both countries were very far from the Beagle area in terms of effective and real sovereignty. Furthermore, Viceroyalty documentation did not include definitions of the Southern limits and lacked related cartography (2005: 69).

Since 1855 agreements and disagreements occurred. A following treaty, signed in 1881, despite clarifying the Argentine jurisdiction over some sectors of the Patagonia region and the Chilean rights over the Estrecho de Magallanes and Cabo de Hornos (Cape Horn), sowed the seeds of future conflict: the route of the Beagle channel was not specified and, therefore, there were no explicit references on the sovereignty of the islands. The Article 3 of this treaty indicated that “(...) all the islands south of the ´Beagle´ Channel up to Cape Horn and those wests of Tierra del Fuego will belong to Chile” (Cancillería Argentina, 1881). The main issue of the problem was about the axis of the canal and if it continued along the entire southern coast of the island of Tierra del Fuego.

In 1893 an Additional and Clarifying Protocol was signed establishing the bi-oceanic principle8. Despite its aim of shedding light on dark spots on the bilateral border, this principle added complexity since the location of two of the three islands and the projection of the respective Maritime spaces were in tension with it: Isla Nueva and Lennox were Atlantic.

In this context, according to Escudé and Cisneros (2000), in 1904 the conflict had its starting point when Argentina began to maintain that the Beagle Channel encircled Navarino Island, leaving the Picton, Nueva and Lennox islands to the east; this thesis was not accepted by Chile who continued to affirm that the course of the canal was parallel to the southern coast of Tierra del Fuego. From that time there would be numerous ideas and turns again, without establishing major changes in positions. However, towards the 1960s, the paralysis of innovative positions stopped with the emergence of the Chilean thesis of the “dry coast”: the border line of the canal would pass through the coast and not through the middle line as Argentina argued (Capeleti and Orso, 2016: 79).

In this framework, the dispute over the three islands of the Beagle Channel reached the 1970s, being one of the biggest unsolved problems in matters of national defense for both States (Guglialmelli, 1979; Otamendi, 2018). Likewise, this dispute went through its most critical period in the second half of the decade (1975-1979), which coincided with the management of the Argentine and Chilean State by two undemocratic military governments and with the high possibility of a warlike confrontation between both States in December of 1978. However, the 1970s began with the intention of Buenos Aires and Santiago to resolve the dispute illustrated in the bilateral request for arbitration to the British government in 1971 (Manzano Iturra, 2014), which would receive the ruling of an arbitration court led by five judges of the International Court of Justice –which had to accept or reject it without making modifications– appointed by consensus of Argentina and Chile.

This arbitration process took place in 1977, being February 18 the day on which the arbitration court ruling was known and on May 2 of the same year the arbitration award was made by Queen Elizabeth II. The final decision of the award established “i) That the Picton, Nueva and Lennox islands belong to the Republic of Chile, together with the islets and rocks immediately adjacent to them” (British Crown, 1977). This arbitration award, a product of the will of both States to reach a diplomatic compromise, far from resolving the conflict, intensified the disputes between both States. It is interesting to mention that the Court based its ruling in the textual interpretation of the Treaty of 1881. Therefore, the Protocol of 1893 and the Pacts of 1902 were neglected as well as the bioceanic principle (Lanús, 1984).

V. a) The area of the Beagle Channel as an axial point

By 1978, the Beagle Channel zone was configured by the Argentine and Chilean de facto governments as an axis with the highest hierarchy in the defense agenda of each country. The fundamental difference in the position of both governments, identifying the components of an axial point, relies on the sovereignty of a set of stable factors (the Nueva, Lennox and Picton islands, the Beagle Channel, other subsidiary water courses and even the Atlantic Ocean; all of them with their geographical and physiographic characteristics, etc.) and variable factors (low population density, economic activities, possible gold deposits, facilities such as guard posts, an aerodrome, administrative structures, etc.).

It is evident that these factors were not important per se, instead their significance was the geopolitical influence that they generated on the capitals of these States (Buenos Aires and Santiago). This influence was an element involved in the process of “geopolitization” of such factors. According to Atencio (1983: 138), “geopolitization” refers to the assessment of the geopolitical influences and the determination of the actions and political measures that are convenient for a State to adopt because of them. For both governments, the assessment of the factors involved in the axial point of the Beagle Channel was fed by various long-standing milestones, some of them more cooperative and other times more conflictive, but with mutual mistrust prevailing and exacerbated during the 1970s.

Within this process of geopolitical appreciation, another feature is visualized in the definition of the nature of every axial point, and it makes it relevant to the disciplinary approach from International Relations: the factors are geopolitically relevant given the existence of “others” outside national borders: Chile and Argentina, respectively. Likewise, another instance of geopolitical appreciation is linked to the connection between various axial points: although the axial points act differently, they are integrated and are not independent of the defense system.

In this context, it is evident that because of the geographical characteristics of the Beagle Channel, in Argentina’s geopolitical appreciation, its proximity to the axial point of the Malvinas Islands or the Argentine Antarctic Sector played an important role, all this considering also the threat of an eventual strategic projection of Chile to the Atlantic Ocean (Gulglialmelli, 1979).

This scenario highlights political definitions regarding which part of the national territory is important for each State and who is the potential threat (the main concern of defense policy) that contribute to shaping foreign actions. On the Argentine side, before the unfavorable award of 1977, within the Government, three tendencies appeared: the army and the navy, which rejected entirely the decision of the Court. Also, some sectors of the Foreign Ministry, “the moderates”, argued that the recitals of the award should be rejected, but the operative section can be accepted. Finally, the most benevolent position was represented by the Legal Counsel that considered accepting the ruling.

The toughest sector prevailed, and Argentina declared the ruling invalid on January 25, 1978, which was announced to de facto Chilean president Augusto Pinochet by the Argentine de facto president Rafael Videla in a meeting that both leaders held in El Plumerillo, Mendoza. It is observed, then, that a defense policy actor contributed to changing perceptions about the outcome of the award and, consequently, to redefining the external concerns of the Argentine State when designing its foreign policy. This foreign policy conditioning situation was crystallized in numerous events. To illustrate this, it is valid to mention the submission of secret telegrams by the Argentine Foreign Ministry to its ambassadors abroad indicating that they will report to the governments where they were based that Argentina was in a situation of war with Chile.

With a very high impact, this conditioning situation led the country to break a long tradition of foreign policy regarding the respect of international commitments (Lacoste, 2004). The vindication of the bi-oceanic principle supported by a particular defense actor was an element that impacted the foreign policy.

This bilateral tension was fueled by the movement of Argentine reserves, troops, and equipment. Meanwhile, Chile established Decree 416 “Straight Baselines” a few days after the arbitration award was known. This Decree indicated that the territorial Sea and the Exclusive Economic Zone of the country should be calculated based on Chilean sovereignty over the territories specified in the award. Argentina, in line with the unilateral nullity of the arbitration award, vigorously rejected that decree arguing that Chile was seeking to question the Cape Horn meridian as the boundary between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, as a result the country was able to question the bioceanic principle, among other issues (Guglialmelli, 1979: 256).

In this scenario, both States were involved in a territorial dispute that, although it was dealt through diplomatic channels, was key for their national defense, with actions in the field of defense that shaped foreign actions. The two countries tried to obtain sovereignty over the islands of the Beagle Channel to improve their defensive position in the region and avoid the potential expansionist intentions of the rival. In other words, both States had the objective of maintaining control and majority sovereign presence in the Beagle Channel, as a priority axial point for both of them (Barreto, 2020). In this line, the objective linked to maintaining control of the channel’s islands meant that each State was perceived by the other as a threat, which is typical in the field of national defense (Battaglino, 2015; Magnani, 2021). From the Argentine side, this perception of threat and these irreconcilable objectives linked to the control of the islands in question led state officials of the de facto government to elaborate an operation aimed at taking sovereign control of the islands. This military plan was named “Operation Sovereignty”9 and it was intended to be executed on December 22, 1978 (Otamendi, 2018).

On the day defined for the operation, the intervention of the Holy See succeeded in canceling it even though the tactical divers were ready to begin amphibious operations. The papal mediation lasted from the end of 1978 until its resolution in 1984 with the signing of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship. This can be analyzed in four stages, depending on the changes that occurred in each country during the negotiations (Laudy, 2000), such as the return to democracy in Argentina. With respect to the 1984 treaty, it marked the end of a territorial dispute that almost led –6 years earlier– both states to war.

In other words, the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Argentina and Chile10 was the legal crystallization of the end of the defense problem that Chile represented for Argentina and that the latter represented for the former. The resolution of this conflict (threats, protection of referent objects, and deployment of offensive and/or deterrent means) linked to a critical axial point within the scope of national defense allowed progress in other areas of the bilateral agenda, such as the construction of mutual trust mechanisms and increased commercial exchange.

The reorientation of the armed forces in relation to the conflict hypothesis led to a change in the pattern of foreign ties for Argentina. The hypothesis of conflict with neighbors and their redirection, for example, to the development of actions within the framework of the United Nations and the dispatch of units to the Persian Gulf and Yugoslavia notably decreased tensions with Chile (Lacoste, 2003: 382-383), evidencing how defense policy can operate in the design of foreign policy.

In 1991, a few years after the settlement of the dispute over the Beagle, the “Santiago Commitment” was signed within the framework of the Organization of American States, an agreement that was a sign of the will of the participating countries to advance in the elimination of conflict hypotheses, the construction of confidence measures, the defense of democracy and the commitment to deepen civil control over military instruments and defense policies. This change in mutual relationship patterns was strongly complemented by the signing of the Economic Complementation Agreement between Argentina and Chile in 1990. This Treaty involved the construction of a gas pipeline connecting Neuquén with Santiago de Chile. Then, by 1991, both countries managed to triple their bilateral trade (Brooke, 1994), as a result, contributing to the increase of both, confidence and the costs of an armed conflict if happens.

The bilateral relationship between both States progressed more towards the coordination of policies in multiple thematic areas, leaving aside the possibility of a warlike confrontation as an instrument to resolve political disputes. This ability to agree, reduce uncertainty, build trust and coordinate policies found its maximum expression in the Maipú Accords11 of 2009, where annual inter-ministerial meetings were scheduled between all the cabinet ministers of the governments of both countries.

Along the previous lines, a set of theoretical and empirical arguments were presented with the aim of addressing the relationship between defense policy and foreign policy from an unconventional point of view. That is, without establishing hierarchies between both public policies or, more specifically, without subordinating defense policy to foreign policy. The analysis made from reviewing the specialized literature showed that this objective would allow us to take a step further in the study of the characteristics of the national defense policy and it contributes to the hierarchization of the discussion regarding the foundations of national defense (Battaglino, 2015).

Thus, the absence of hierarchy in the relationship between both public policies was highlighted by considering both as philosophical subsidiaries of the same socio-state framework. In this setting, the concept “axial point” was used to represent a framework in which both defense and foreign policy have their raison d’être. Of course, this does not mean approaching a position that considers them endogenously determined; on the contrary, the axial point reaches its full configuration by taking into account several considerations coming from the external environment.

The development of the article supported the argument that defense policy can impact foreign policy to the extent that it contributes to changing perceptions regarding which actors are threatening and consequently redefining the external concerns that States have when designing their foreign policy.

The 1970s in Argentina and Chile were characterized by a dispute regarding the sovereignty of three islands in the Beagle Channel, becoming one of the biggest unresolved problems in matters of national defense for both States. This dispute led them to establish a relationship based on a logic of enmity/rivalry (Wendt, 1999). The resolution of the sovereignty problem in 1984 with the Treaty of Peace and Friendship, implied modifications in various factors related to the national defense of the Argentine State (threats, protection of referent objects, and deployment of offensive and/or deterrent means), part of a critical axial point within the governmental scope of the Ministry of Defense. The fundamental issue is that this was a necessary condition for the beginning of another type of bilateral relation increasing the mechanisms of mutual trust or commercial exchange, among others.

Since the resolution of the dispute, the logic of friendship has prevailed in the bilateral bond. Although the agenda was notably diversified and defense issues are part of a broad thematic list, due to the Southern condition of both countries and the growing challenges that geographic space presents for the future. The defense agenda can influence and promote cooperative bilateral relations within the framework of various joint activities that allow us to think of a network of stable and variable geopolitical factors that are geopolitically appreciated by Buenos Aires and Santiago as an axial point of binational features. Both States and their citizens have an austral destination and, therefore, the need to locate axial points in that area. Facing the challenges together may be a way to get higher profits in a context of potential geopolitical tensions to come (Manzano Iturra, 2021).

Acuerdo de Complementación Económica N° 16 entre la República Argentina y la República de Chile, 1990. Retrieved on July 23, 2021 from http://www.sice.oas.org/trade/argchi/acuerdo_s.asp

Atencio, J. (1983). Qué es Geopolítica, Buenos Aires: Pleamar.

Barreto, M. (2020). “El sistema de defensa argentino. Aportes de la Geopolítica y las Relaciones Internacionales para su conceptualización”, in Magnani, Ezequiel y Barreto Maximiliano (eds.), Puntos axiales del sistema de defensa argentino. Los desafíos de pensar la defensa a partir del interés nacional, Rosario: Universidad Nacional de Rosario, pp. 21-34.

Battaglino, J. (2015). “Fundamentos Olvidados de la Política de Defensa: Reflexiones a partir del Caso Argentino”, Revista Brasileira de Estudos de Defesa, 2(2). July-December, pp. 197-216.

---- (2019). “Threat Construction and Military Intervention in Internal Security. The Political Use of Terrorism and Drug Trafficking in Contemporary Argentina”, Latin American Perspectives. X, pp. 1-15.

Busso, A. et al. (2016). Modelos de desarrollo e inserción internacional: aportes para el análisis de la política exterior argentina desde la redemocratización 1983-2011, Rosario : UNR Editora.

Busso, A. and Barreto, M. (2020). “Política exterior y de defensa en Argentina. De los gobiernos kirchneristas a Mauricio Macri (2003-2019)”, URIVO. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios de Seguridad. 27, pp.74-93.

British Crown. (1977). Argentina-Chile: Beagle Channel Arbitration. Retrieved on July 14, 2021 from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-legal-materials/

Brooke, J. (08/04/1994). The New South Americans: Friends or Partners? New York Times. Retrieved on July 23, 2021 from https://www.nytimes.com/1994/04/08/world/the-new-south-americans-friends-and-partners.html

Calderón, E. (2018). “La defensa argentina del siglo XXI: Del activismo subregional al globalismo relativo”, Revista Política y Estrategia, 131, pp. 57–79.

Cancillería Argentina. (1881). Tratado de Límites entre la República Argentina y la República de Chile. Retrieved on June 21, 2021 from https://tratados.cancilleria.gob.ar/

---- (1984). Tratado de Paz Argentino-Chileno. Retrieved on June 20, 2021 from https://tratados.cancilleria.gob.ar/

Capeletti, D. y Orso, J. (2016). “La transformación de conflictos en las relaciones bilaterales chileno-argentinas. El caso del Beagle”, Perspectivas Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 2, July-December, pp. 76-95.

Castaño, P. (2003). “La distinción entre lo doméstico y lo internacional como sustrato epistemológico de las relaciones internacionales”. Colombia Internacional, n° 56-57, pp. 132-147. Retrieved on June 15, 2021 from https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint56-57.2003.09

Compromiso de Santiago con la Democracia y la Renovación del Sistema Interamericano. (1991). Retrieved on July 23, 2021 from https://biblioteca.iidh-jurisprudencia.ac.cr/index.php/documentos-en-espanol/legislacion-internacional/sistema-interamericano/instrumentos-declarativos/2115-compromiso-de-santiago-con-la-democracia-y-la-renovacion-del-sistema-interamericano-santiago-1991/file

Church, J. M. (2008). “La crisis del canal de Beagle”, Estudios Internacionales, 41(161), pp. 7-33.

Eissa, S. (2013). “Redefiniendo la política de defensa: hacia un posicionamiento estratégico defensivo regional”. Revista SAAP, 7(1). May, pp. 41-64.

---- (2017). “Defensa Nacional: consideraciones para un enfoque analítico”, Relaciones Internacionales, 26(53). December, pp. 246-265. doi.org/10.24215/23142766e021

Escudé, C. and Cisneros, A. (2000). Historia General de las Relaciones Exteriores de la República Argentina. Buenos Aires: Consejo Argentino para las Relaciones Internacionales (CARI) and Nuevohacer-Gel.

Frenkel, A. (2020). “Argentina en el Consejo de Defensa Suramericano de la Unasur (2015-2018)”, Estudos internacionais, 8(1), pp. 44-63.

Guglialmelli, J. (1979). Geopolítica del Cono Sur. Argentina: El Cid Editor.

Lacoste, P. (2003). La imagen del otro en las relaciones de la Argentina y Chile (1534-2000). Buenos Aires : Fondo de Cultura Económica.

---- (2004). “La disputa por el Beagle y el papel de los actores no estatales argentinos”, Revista Universum. 1(19), pp. 86-109.

---- (2005). “El conflicto del Beagle. Nueva Mirada”, Todo es Historia, n° 461. December, pp. 68-79.

Lanús, J. A. (1984). De Chapultepec al Beagle. Política Exterior Argentina, Buenos Aires: Emecé, pp. 499-530.

Lasagna, M. (1995). “Las determinantes internas de la política exterior: un tema descuidado en la teoría de la política exterior”, Estudios Internacionales. 28(111), pp. 387-409.

Laudy, M. (2000). “The Vatican Mediation of the Beagle Channel Dispute: Crisis Intervention and Forum Building” en Words Over War: Mediation and Arbitration to Prevent Deadly Conflict, Melanie Greenberg, John H. Barton y Margaret E. McGuiness (eds.), Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Lijphart, A. (1971). “Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method”, The American Political Science Review, 65(3).

Magnani, E. and Barreto, M. (2020). Puntos axiales del sistema de defensa argentino. Los desafíos de pensar la defensa a partir del interés nacional. Rosario: Universidad Nacional de Rosario, pp. 1-246.

Magnani, E. and Altieri, M. (2020). “Brasil y el cambio en su estrategia de defensa: de la autonomía a la aquiescencia (2003-2020)”, Perspectivas Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 5(10), pp.102-129

Magnani, E. (2021). “La Dimensión Estratégica de la Política de Defensa: apuntes para su conceptualización desde el caso argentino”, Revista SAAP. 15(1). May, pp. 103-129.

Manzano Iturra, K. I. (2014). “Arbitraje y Mediación. Los medios jurídicos tras el conflicto del Beagle”, Revista de Historia Americana y Argentina. 49(1), pp. 47-64.

---- (2021). “La disputa por el canal de Beagle y sus consecuencias geopolíticas para la zona austral-antártica”, Revista Científica General José María Córdova. 19(35), pp. 799-815.

Otamendi, A. (2018). Aires de guerra sobre las aguas de tierra del fuego. Buenos Aires: Instituto de Publicaciones Navales.

Paradiso, J. (1993). Debates y trayectoria de la política exterior argentina. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Emece.

Russell, R. (1990). “Política exterior y toma de decisiones en América Latina: aspectos comparativos y consideraciones teóricas“, in Russell Roberto (ed.), Política exterior y toma de decisiones en América Latina, Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano, pp. 255-274.

---- (1992a). “Lo nuevo del nuevo orden mundial”, Work presented at the Seminar ‘La política exterior argentina en la post Guerra Fría’, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Buenos Aires.

---- (1992c). La política exterior argentina en el nuevo orden mundial. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

---- (1992b). Enfoques teóricos y metodológicos para el estudio de la política exterior. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

Russell, R. and Tokatlian, J. G. (2013). “América Latina y su gran estrategia: entre la aquiescencia y la autonomía”, Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals. n°104, pp. 157-180.

Rosenau, J. (2006). The Study of World Politics, Nueva York: Ed. Rouldedge.

Saín, M. (2000). “Quince años de legislación democrática sobre temas militares y de defensa (1983-1998)”, Desarrollo Económico. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 40(157), pp. 121-142.

Saint Pierre, H. (2012). “Fundamentos para pensar la distinción entre defensa y seguridad”, en RESDAL (ed.), Atlas comparativo de la Defensa en América Latina y el Caribe, Buenos Aires : RESDAL, pp. 42-43.

Soares de Lima, M. (1994). “Ejes analíticos y conflicto de paradigmas en la política exterior brasileña”, América Latina/Internacional. 1(2), pp. 27-46.

Tokatlián, J. G. and Pardo, R. (1990). “La teoría de la interdependencia: ¿una alternativa al realismo?”, Estudios Internacionales. 91, pp. 339-382.

Tokatlián, J. G. and Caravajal, L. (1995). “Autonomía y política exterior en América Latina: un debate abierto, un futuro incierto”, Revista CIDOB D’Afers Internacionals. 28, pp. 7-31.

Tokatlián, J. G. and Russell, R. (1998). Neutralidad Política mundial. Una mirada desde las relaciones internacionales. Estudios. Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de las Actividades del Nazismo en la Argentina, 24-39.

Tokatlián, J. G. and Merke, F. (2014). “Instituciones y actores de la política exterior como política pública”, en Acuña, Carlos (comp.), Dilemas del Estado Argentino, Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores, pp. 245-312.

Tratado de Maipú de Integración y Cooperación entre la República de Chile y la República Argentina. (2009). Retrieved on July 23, 2021 from https://www.senado.gob.ar/prensa/17199/noticias

Van Klaveren, A. (1992). “Entendiendo las políticas exteriores latinoamericanas: modelo para armar”, Estudios internacionales. N° 98, pp. 169-216.

Villar Gertner, A. (2014). “The Beagle Channel frontier dispute between Argentina and Chile: Converging domestic and international conflicts”, International Relations, 28(2), pp. 207-227.

Wendt, A. (1999). Social theory of international politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

1 This article is an extended version of a presentation made in the XV Congress of the Argentine Society of Political Analysis during November 2021. The presentation won the award “Carlos Escudé” for the best presentation in International Relations.

2 Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. Departamento de Ciencia Política y Estudios Internacionales. Becario doctoral del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de Argentina (CONICET). Profesor Auxiliar. Magíster en Estudios Internacionales.

Correo electrónico: ezequielmagnani11@gmail.com

3 Universidad Católica Argentina. Facultad Teresa Ávila. Universidad Nacional de Rosario. Facultad de Ciencia Política y Relaciones Internacionales. Profesor Asistente. Licenciado en Relaciones Internacionales. Correo electrónico: maximilianobarreto@uca.edu.ar

4 The concept “basic consensus” was first used by the academic Marcelo Saín (2000). It refers to the agreement of the Argentinian political bodyregarding national defense establishing that there should be (1) a clear distinction between national defense and internal security, (2) a strict political command of the armed forces, and (3) a termination of conflict hypothesis with neighboring States.

5 Internally, the nature of violence is protective and ordering since the foundation of the pact is the protection and security of the subject (Saint Pierre, 2012: 42).

6 If it exists, it responds to a social construction.

7 For more details on the definition of an axial point see: Barreto, Maximiliano (2020), “El sistema de defensa argentino. Aportes de la Geopolítica y las Relaciones Internacionales para su conceptualización”, en Magnani, Ezequiel y Barreto, Maximiliano (eds.) Puntos Axiales del Sistema de Defensa Argentino, Rosario: UNR Editora, pp. 21-34.

8 This principle established the exclusivity of Argentina to the Atlantic Ocean and Chile to the Pacific Ocean, neither of the two countries being able to claim sovereignty in the other ocean (Capeletti and Orso, 2016: 78).

9 This operation included a planning that considered military maneuvers on “several continental fronts, with areas of responsibility that corresponded to the three armed forces, which would engage in different complementary and simultaneous maneuvers in the south, center and north of the country” (Otamendi, 2018: 37).

10 Especially as regards the seventh article of the Treaty, where the maritime delimitation of both States is clearly established. In this sense, although Chile managed to maintain the sovereignty of the disputed islands of the Beagle Channel, the agreement specified that the oceanic principle remained in force and that Chile could not claim territorial sea for 11 miles and the Exclusive Economic Zone for 200 miles to the East.

11 The Maipú Accords, officially Tratado de Maipú de Integración y cooperación entre la República de Chile y la República Argentina, is a bilateral treaty that seeks to foster and reinforce the integration of both States in the cultural, social, commercial, economic, and political fields. In order to achieve that goal, the treaty establishes annual inter-ministerial meetings. In addition, to reinforcing the idea of the positive bilateral relations between both countries, the treaty mentions that it complements the Tratado de Paz y Amistad entre Argentina y Chile signed in 1984, which is known as the one that ended completely the territorial disputes between both States.

Fecha de recepción: 17 de marzo del 2022 •

Fecha de aceptación: 4 de mayo del 2022

Fecha de publicación: 13 de junio del 2022

Revista de Relaciones Internacionales por Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional.

Equipo Editorial

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica. Campus Omar Dengo

Apartado postal 86-3000. Heredia, Costa Rica